Chapter 1

I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family. I had two elder brothers, one of which was lieutenant-colonel to an English regiment of foot in Flanders, and was killed at the battle near Dunkirk against the Spaniards; what became of my second brother I never knew, any more than my father or mother did know what had become of me.

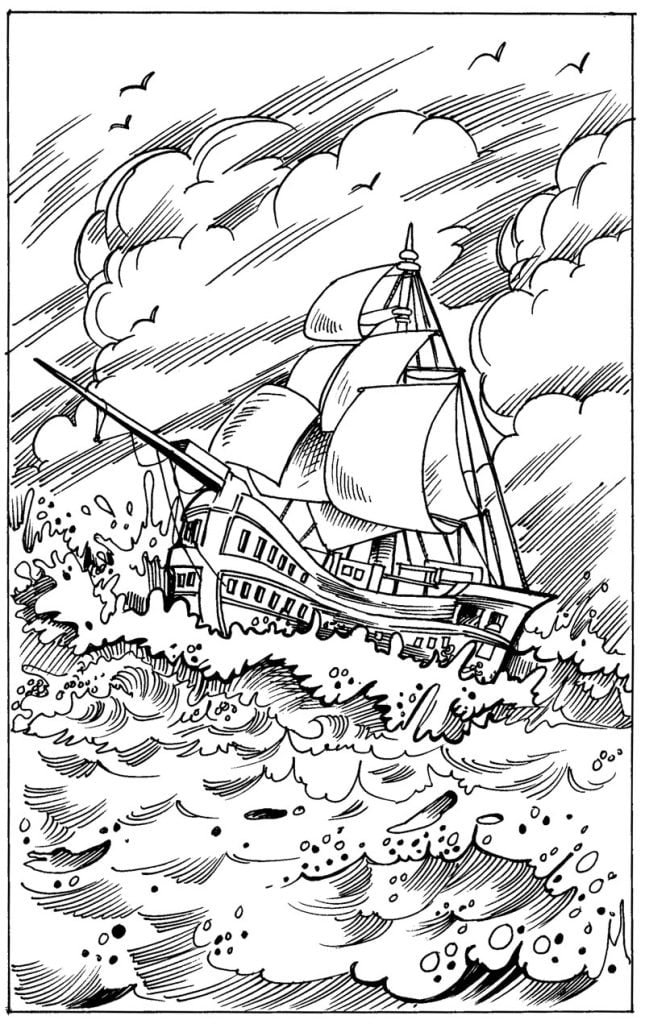

One day at Hull, where I went casually, one of my companions going to sea to London in his father’s ship, and prompting me to go with them, with the common allurement of seafaring men—namely, that it should cost me nothing for my passage. Never any young adventurer’s misfortunes, I believe, began sooner, or continued longer than mine. The ship had no sooner got out of the Humber than the wind began to blow, and the waves to rise in a most frightful manner. As I had never been to sea before, I was most inexpressibly sick in body, and terrified in my mind.

By this time it blew a terrible storm indeed. Now I began to see terror and amazement in the faces even of the seamen themselves.

The storm was so violent that I saw what is not often seen—the master, the boatswain, and some others more sensible than the rest, at their prayers, and expecting every moment when the ship would go to the bottom. In the middle of the night, and under all the rest of our distresses, one of the men that had been down on purpose to see, cried out we had sprung a leak. Another said there was four foot of water in the hold.

Then all hands were called to the pump. At that very word my heart, as I thought, died within me, and I fell backwards upon the side of my bed where I sat, into the cabin. However, the men roused me, and told me that I was able to do nothing before was as well able to pump as another, at which I stirred up and went to the pump.

We worked on; but the water was increasing in the hold. It was apparent that the ship would founder; and though the storm began to abate a little, yet, as it was not possible she could swim till we might run into a port, so the master continued firing guns for help, and a light ship, who had rid it out just ahead of us, ventured a boat out to help us. It was with the utmost hazard the boat came near us. But it was impossible for us to get on board, or for the boat to lie near the side of the ship, till at last, the men rowing very heartily, and venturing their lives to save ours. Our men cast them a rope over the stern with a buoy to it, and then veered it out a great length, which they, after great labour and hazard, took hold of, and we hauled them close under our stern, and got all into their boat. It was of no purpose for them or us after we were in the boat to think of reaching their own ship. So all agreed to let her drive, and only to pull her in towards shore as much as we could. Our master promised them, that if the boat was staved upon shore, he would make it good to their master. So, partly rowing and partly driving, our boat went away to the northward, sloping towards the shore almost as far as Winterton Ness.

We were not much more than a quarter of an hour out of our ship when we saw her sink. Then I understood for the first time what was meant by a ship foundering in the sea.

While we were in this condition, the men yet labouring at the oar to bring the boat near the shore, we could see, when our boat, mounting the waves, a great many people running along the shore to assist us when we should come near. But we made but slow way, nor were we able to reach the shore, till, being past the lighthouse at Winterton, the shore falls off to the westward towards Cromer. So the land broke off a little the violence of the wind. Here we got in, and though not without much difficulty, got all safe on shore, and walked afterwards on foot to Yarmouth, where, as unfortunate men, we were used with great humanity, as well by the magistrates of the town. They assigned us good quarters, as by particular merchants and owners of ships, and had money given us sufficient to carry us either to London or back to Hull, as we thought fit.

Had I now had the sense to have gone back to Hull, and have gone home, I had been happy. But my ill-fate pushed me on now with an obstinacy that nothing could resist.

My comrade, who had helped to harden me before, and who was the master’s son, was now less forward than I. The first time he spoke to me after we were at Yarmouth, it appeared his tone was altered, and looking very melancholy, and shaking his head, asked me how I did, and telling his father who I was, and how I had come this voyage only for a trial, in order to go farther abroad. His father, turning to me with a very grave and concerned tone, said “Young man,” says he, “you ought never to go to sea any more; you ought to take this for a plain and visible token that you are not to be a seafaring man.”

We parted soon after, for I made him little answer, and I saw him no more. Which way he went I didn’t know. As for me, having some money in my pocket. I travelled to London by land; and there, as well as on the road, had many struggles with myself—what course of life I should take, and whether I should go home or go to sea.

As to going home, shame opposed the best motions that offered to my thoughts. It immediately occurred to me how I should be laughed at among the neighbours, and should be ashamed to see, not my father and mother only, but even everybody else.

It was my lot first of all to fall into pretty good company in London, which does not always happen to such loose and unguided young fellows as I then was, the devil generally not omitting to lay some snare for them very early. But it was not so with me. I first fell acquainted with the master of a ship who had been on the coast of Guinea; and who, having had very good success there, was resolved to go again. He took a fancy to my conversation, which was not at all disagreeable at that time, hearing me say I had a mind to see the world, told me if I would go to the voyage with him I should be at no expense. I should be his messmate and his companion; and if I could carry anything with me, I should have all the advantage of it that the trade would admit, and perhaps I might meet with some encouragement.

I embraced the offer. Entering into a strict friendship with this captain, who was an honest and plain-dealing man, I went the voyage with him. I carried a small adventure with me, which, by the disinterested honesty of my friend the captain, I increased very considerably. I carried about £40 in such toys and trifles as the captain directed me to buy. This £40 I had mustered together by the assistance of some of my relations whom I corresponded with, and who, I believed, got my father, or at least my mother, to contribute so much as that to my first adventure.

This was the only voyage which I might say was successful in all my adventures, and which I owed to the integrity and honesty of my friend the captain, under whom also I got a competent knowledge of mathematics and the rules of navigation, learned how to keep an account of the course of the ship, take an observation, and, in short, to understand some things that were needful to be understood by a sailor. As he took delight to introduce me, I took delight to learn. In a word, this voyage made me both a sailor and a merchant; for I brought home five pounds nine ounces of gold dust for my adventure, which yielded me in London at my return almost £300. This filled me with those aspiring thoughts which had since so completed my ruin.