Chapter-11

When the others had gone, Elizabeth, as if wishing to increase her dislike of Mr. Darcy as much as possible, read all the letters which Jane had written. They contained no complaint, but in all of them there was a note of sadness, very unlike Jane’s usual cheerfulness. Mr. Darcy’s shameful boast that he was the cause of all this made Elizabeth even more angry. It was some comfort to think that his visit to Rosings would soon end.

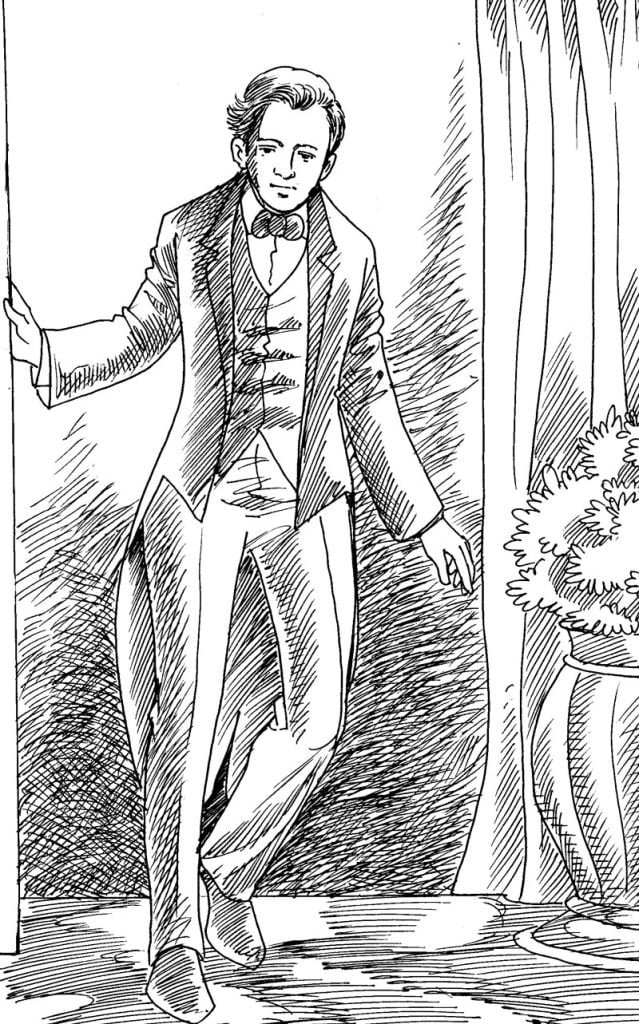

She was suddenly aroused by the sound of the door bell. To her utter amazement, Mr. Darcy walked into the room. In a hurried manner, he immediately began to ask about her health, suggesting that this was the reason for his visit. She answered with cold politeness. He sat down for a few moments and then, getting up again, walked about the room. Elizabeth was surprised, but said not a word. After a silence of several minutes he came towards her in an excited manner and thus began : “I have struggled in vain. It will not do. I cannot restrain my feelings. You must allow me to tell you how passionately I admire and love you.”

Elizabeth’s astonishment was beyond expression. She stared, blushed, doubted and was silent. This he considered, enough encouragement. The confession of all he felt and had long felt for her immediately followed.

He spoke well, but he mentioned other things beside his love for her. He was equally eloquent on the subject of his pride. His sense of her inferiority—of his humiliation—of the difficulty of accepting her family were described with a warmth which was unlikely to please Elizabeth.

The next morning Elizabeth had not yet recovered from the surprise of what had happened; it was impossible to think of anything else. She could do no work at all, and she decided soon after breakfast to give herself some fresh air and exercise.

After walking two or three times up and down the road she stopped for a moment to look in the park. Every day the trees there were becoming more green. She was on the point of continuing her walk when she saw a gentleman inside the park. Fearful of meeting Mr. Darcy, she turned away immediately. But the person, who was now near enough to see her, stepped forward eagerly calling her name. The voice proved him to be Mr. Darcy and she moved again towards the gate. He had by that time reached it also and, holding out a letter, which she took, he said with haughty calm, “I have been walking here for sometime in the hope of meeting you. Will you be good enough to read that letter?” And then, with a slight bow, he turned again into the trees and was soon out of sight.

With no pleasure but great curiosity Elizabeth opened the letter. The envelope contained two sheets of note paper, written throughout in a very small, neat hand. It had been written at eight o’clock that morning and was as follows:

“Do not be alarmed, madam, by the fear that this letter will repeat those feelings which were last night so disgusting to you. I do not wish to pain you or humble myself, by renewing offers which cannot be too soon forgotten. I should never have written this letter except to defend my character. You must forgive my demand for your attention. You will give it unwillingly, I know, but I ask it of your sense of justice.”

“Last night you accused me of two very different offences. The first was that I had separated Mr. Bingley and your sister, and the second that I had, in defiance of honour and humanity, ruined the hopes of Mr. Wickham. From the severity of your blame last night, I shall hope in future to be spared, when the following account of my actions is read. If I offend you in explaining my feelings, I can only say I am sorry.”

“I had not been long in Hertfordshire before I saw that Bingley preferred your elder sister to any other young woman in the county. But it was not until the evening of the dance at Netherfield that I began to fear the affair might be serious. He had often been in love before. From that moment I watched my friend carefully. I could see that his affection for Miss Bennet was greater than anything I had ever seen in him. I also watched your sister. Her look and manners were open, cheerful and charming as ever, but without any sign of particular affection. I was sure that although she enjoyed his attention she did not share his feelings. Perhaps I was wrong.”

“If so—and if I inflicted pain upon her—your resentment was reasonable. But I declare that the calm of your sister’s manner and face might have deceived anyone; it seemed to me that, although her temper was agreeable, her heart would not easily be touched.”

“My objections to the marriage were not merely the low rank of your family. This could not be so great an evil to my friend as to me. But there were other causes which must be stated briefly. The activities of your mother’s brothers as tradesmen and lawyers were not as objectionable as the lack of good manners shown by herself, and by your younger sisters—forgive me—it pains me to offend you. Let it be some comfort that you and your elder sister do not share any of this criticism. I will only say that on that evening at Netherfield my opinion of all concerned was confirmed, and I determined to save my friend from what I thought a most unhappy marriage.”

“The next day he left Netherfield for London, with the intention of soon returning. His sister’s uneasiness had also been aroused and I discussed it with them. Realizing that there was no time to be lost, we decided to join him at once in London. There I undertook the task of pointing out to my friend the certain evils of his choice. But I do not suppose that my warnings would have had any permanent effect if I had not assured him, without hesitation, of your sister’s indifference. He had believed that she loved him as sincerely as he loved her. But Bingley has great natural modesty and he depends more on my judgment than on his own. It was not difficult to convince him that he had deceived himself. It was no trouble to persuade him not to return to Hertfordshire. I cannot blame myself for having done this.”

“On this subject I have nothing more to say, no other apology to offer. If I have hurt your sister, it was done unintentionally.”

“With regard to that other, more serious, accusation of having injured Mr. Wickham, I can only protect myself by telling you the whole story of his connection with my family.”

“Mr. Wickham is the son of a very respectable man who for many years managed the Pemberley estates. My father appreciated his good work and was therefore glad to help George Wickham, who was his god-son. My father sent him to school and afterwards to Cambridge—most valuable assistance, since his own father, who had an extravagant wife, could never have given him a gentleman’s education. My father enjoyed the company of this young man—whose manners were always charming. He hoped the Church would be his profession and intended to provide a ‘living’ for him.”

“As for myself, many, many years ago I began to think of George Wickham in a very different manner. His evil inclinations could be seen more easily by another young man of the same age as himself. Here again I shall give you pain—I do not know how much. But whatever your feelings are for Mr. Wickham I must tell you his real character.”

“My excellent father died about five years ago and in his will he particularly asked me to help Mr. Wickham in whatever profession he chose. If he went into the Church my father wished me to give him a valuable family living when it was vacant. He also left him a thousand pounds. Mr. Wickham’s own father died soon after. Within six months George Wickham wrote to tell me that as he had decided not to enter the Church, he would not need the ‘living’ and he hoped that I would give him some money to help him study law. I hoped that he was sincere and was quite ready to help him. I knew that Mr. Wickham ought not to be a clergyman. The business was therefore soon settled. He gave up all claim to assistance in a career in the Church and accepted in exchange three thousand pounds.”

“We had nothing more to do with each other for three years. I believe he lived in town, but his study of the law was a mere pretence. His life was one of idleness and drunkenness. But three years later he wrote to me again, to ask for the ‘living’, which had once been intended for him. He was heavily in debt. The law had been an unprofitable study and he had now decided to become a clergyman.”