Chapter 10

Next morning we all made our escape towards the mountains. All day long, we could not get into the waters of the ocean as the storm raged in fury. We found shelter in a cave that night. On the following night the storm abated somewhat. In the morning we went inside the village to seek for food, being so famished with hunger that we lost all feeling of danger and all wish to escape. Suddenly, we were seized by three warriors who bound our wrists and thrust us into the prison.

Thus we sat for some time in deep silence. Soon after, we heard footsteps at the entrance of the cave, and immediately our jailer entered. We were so much accustomed to his regular visits, however, that we paid little attention to him, expecting that he would set down our meagre fare, as usual, and depart. But, to our surprise, instead of doing so, he advanced towards us with a knife in his hand, and, going up to Jack, he cut the thongs that bound his wrists, then he did the same to Peterkin and me!

For fully five minutes we stood in speechless amazement, with our freed hands hanging idly by our sides. The first thought that rushed into my mind was, that the time had come to put us to death; and although, as I have said before, we actually wished for death in the strength of our despair, now that we thought it drew really near I felt all the natural love of life revive in my heart, mingled with a chill of horror at the suddenness of our call.

But I was mistaken. After cutting our bonds, the savage pointed to the mouth of the cave, and we marched, almost mechanically, into the open air. Here, to our surprise, we found the teacher standing under a tree, with his hands clasped before him, and the tears trickling down his dark cheeks. On seeing Jack, who came out first, he sprang towards him, and clasping him in his arms, exclaimed—

“Oh! my dear young friend, through the great goodness of God you are free!”

“Free!” cried Jack.

“Ay, free,” repeated the teacher, shaking us warmly by the hands again and again, “free to go and come as you will. The Lord has unloosed the bands of the captive and set the prisoners free. A missionary has been sent to us, and Tararo has embraced the Christian religion! The people are even now burning their gods of wood! Come, my dear friends, and see the glorious sight.”

We could scarcely credit our senses. So long had we been accustomed in our cavern to dream of deliverance, that we imagined for a moment this must surely be nothing more than another vivid dream. Our eyes and minds were dazzled, too, by the brilliant sunshine, which almost blinded us after our long confinement to the gloom of our prison, so that we felt giddy with the variety of conflicting emotions that filled our throbbing bosoms; but as we followed the footsteps of our sable friend, and beheld the bright foliage of the trees, and heard the cries of the paroquets, and smelt the rich perfume of the flowering shrubs, the truth, that we were really delivered from prison and from death, rushed with overwhelming power into our souls, and, with one accord, while tears sprang to our eyes, we uttered a loud long cheer of joy.

It was replied to by a shout from a number of the natives who chanced to be near. Running towards us, they shook us by the hand with every demonstration of kindly feeling. They then fell behind, and, forming a sort of procession, conducted us to the dwelling of Tararo.

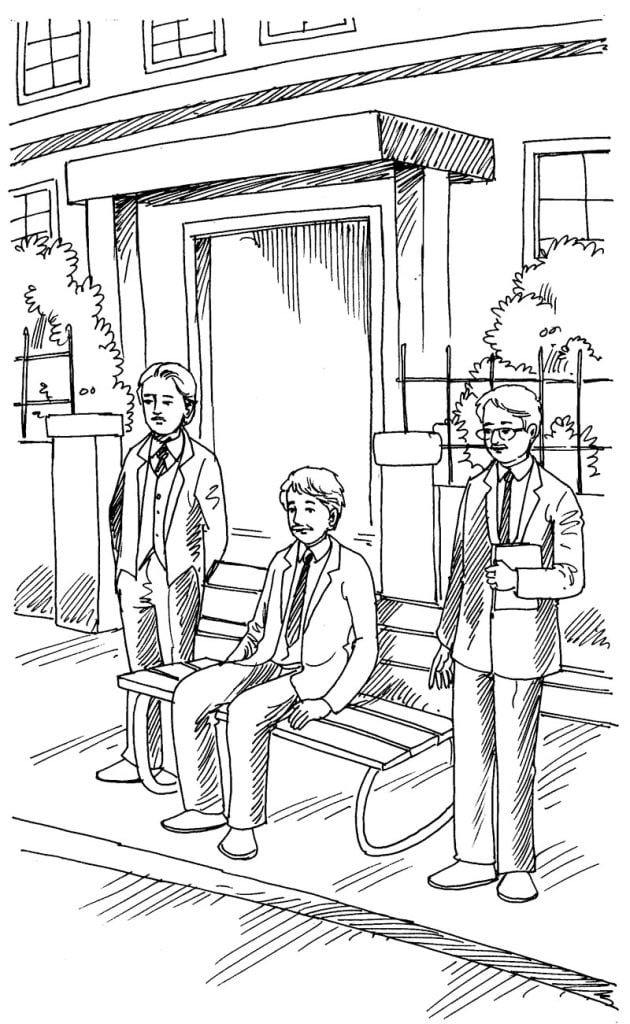

The scene that met our eyes here was one that I shall never forget. On a rude bench in front of his house sat the chief. A native stood on his left hand, who, from his dress, seemed to be a teacher. On his right stood an English gentleman, who, I at once and rightly concluded, was a missionary. He was tall, thin, and apparently past forty, with a bald forehead, and thin grey hair. The expression of his countenance was the most winning I ever saw, and his clear grey eye beamed with a look that was frank, fearless, loving, and truthful. In front of the chief was an open space, in the centre of which lay a pile of wooden idols, ready to be set on fire; and around these were assembled thousands of natives, who had come to join in or to witness the unusual sight. A bright smile overspread the missionary’s face as he advanced quickly to meet us, and he shook us warmly by the hands.

“I am overjoyed to meet you, my dear young friends,” he said, “My friend, and your friend, the teacher, has told me your history; and I thank our Father in heaven, with all my heart, that he has guided me to this island, and made me the instrument of saving you.”

We thanked the missionary most heartily, and asked him in some surprise how he had succeeded in turning the heart of Tararo in our favour.

“I will tell you that at a more convenient time,” he answered, “meanwhile we must not forget the respect due to the chief. He waits to receive you.”

In the conversation that immediately followed between us and Tararo, the latter said that the light of the gospel of Jesus Christ had been sent to the island, and that to it we were indebted for our freedom. Moreover, he told us that we were at liberty to depart in our schooner whenever we pleased, and that we should be supplied with as much provision as we required. He concluded by shaking hands with us warmly, and performing the ceremony of rubbing noses.

This was indeed good news to us, and we could hardly find words to express our gratitude to the chief and to the missionary.

“And what of Avatea?” inquired Jack.

The missionary replied by pointing to a group of natives in the midst of whom the girl stood. Beside her was a tall, strapping fellow, whose noble mien and air of superiority bespoke him a chief of no ordinary kind.

“That youth is her lover. He came this very morning in his war-canoe to treat with Tararo for Avatea. He is to be married in a few days, and afterwards returns to his island home with his bride!”

“That’s capital,” said Jack, as he stepped up to the savage and gave him a hearty shake of the hand. “I wish you joy, my lad—and you too, Avatea.”

As Jack spoke, Avatea’s lover took him by the hand and led him to the spot where Tararo and the missionary stood, surrounded by most of the chief men of the tribe. The girl herself followed, and stood on his left hand while her lover stood on his right, and, commanding silence, made the following speech, which was translated by the missionary:—

“Young friend, you have seen few years, but your head is old. Your heart also is large and very brave. I and Avatea are your debtors, and we wish, in the midst of this assembly, to acknowledge our debt, and to say that it is one which we can never repay. You have risked your life for one who was known to you only for a few days. But she was a woman in distress, and that was enough to secure to her the aid of a Christian man. We, who live in these islands of the sea, know that the true Christians always act thus. Their religion is one of love and kindness. We thank God that so many Christians have been sent here—we hope many more will come. Remember that I and Avatea will think of you and pray for you and your brave comrades when you are far away.”

To this kind speech Jack returned a short sailor-like reply, in which he insisted that he had only done for Avatea what he would have done for any woman under the sun. But Jack’s forte did not lie in speech-making, so he terminated rather abruptly by seizing the chief’s hand and shaking it violently, after which he made a hasty retreat.

“Now, then, Ralph and Peterkin,” said Jack, as we mingled with the crowd, “it seems to me that the object we came here for having been satisfactorily accomplished, we have nothing more to do but get ready for sea as fast as we can, and hurrah for dear old England!”

“That’s my idea precisely,” said Peterkin, endeavouring to wink, but he had wept so much of late, poor fellow, that he found it difficult, “however, I’m not going away till I see these fellows burn their gods.”

Peterkin had his wish, for, in a few minutes afterwards, fire was put to the pile, the roaring flames ascended, and, amid the acclamations of the assembled thousands, the false gods of Mango were reduced to ashes!

The time soon drew near when we were to quit the islands of the South Seas; and, strange though it may appear, we felt deep regret at parting with the natives of the island of Mango; for, after they embraced the Christian faith, they sought, by showing us the utmost kindness, to compensate for the harsh treatment we had experienced at their hands; and we felt a growing affection for the native teachers and the missionary, and especially for Avatea and her husband.

Before leaving, we had many long and interesting conversations with the missionary, in one of which he told us that he had been making for the island of Raratonga when his native-built sloop was blown out of its course, during a violent gale, and driven to this island. At first the natives refused to listen to what he had to say; but, after a week’s residence among them, Tararo came to him and said that he wished to become a Christian, and would burn his idols. He proved himself to be sincere, for, as we have seen, he persuaded all his people to do likewise. I use the word persuaded advisedly; for, like all the other Feejee chiefs, Tararo was a despot and might have commanded obedience to his wishes; but he entered so readily into the spirit of the new faith that he perceived at once the impropriety of using constraint in the propagation of it. He set the example, therefore; and that example was followed by almost every man of the tribe.

During the short time that we remained at the island, repairing our vessel and getting her ready for sea, the natives had commenced building a large and commodious church, under the superintendence of the missionary, and several rows of new cottages were marked out; so that the place bid fair to become, in a few months, as prosperous and beautiful as the Christian village at the other end of the island.

After Avatea was married, she and her husband were sent away, loaded with presents, chiefly of an edible nature. One of the native teachers went with them, for the purpose of visiting still more distant islands of the sea, and spreading, if possible, the light of the glorious gospel there.

As the missionary intended to remain for several weeks longer, in order to encourage and confirm his new converts, Jack and Peterkin and I held a consultation in the cabin of our schooner—which we found just as we had left her, for everything that had been taken out of her was restored. We now resolved to delay our departure no longer. The desire to see our beloved native land was strong upon us, and we could not wait.

Three natives volunteered to go with us to Tahiti, where we thought it likely that we should be able to procure a sufficient crew of sailors to man our vessel; so we accepted their offer gladly.

It was a bright clear morning when we hoisted the snow-white sails of the pirate schooner and left the shores of Mango. The missionary, and thousands of the natives, came down to bid us God-speed, and to see us sail away. As the vessel bent before a light fair wind, we glided quickly over the lagoon under a cloud of canvass.

Just as we passed through the channel in the reef the natives gave us a loud cheer; and as the missionary waved his hat, while he stood on a coral rock with his grey hair floating in the wind, we heard the single word “Farewell” borne faintly over the sea.

❒