Chapter 2

Now they had gone three miles and more, and came to Sir John’s lodge-gates.

Very grand lodges they were, with very grand iron gates and stone gate-posts, and on the top of each a most dreadful bogy, all teeth, horns and tail.

Grimes rang at the gate, and out came a keeper on the spot. He opened the gate.

“I was told to expect you,” he said.

The keeper went with them. To Tom’s surprise, he and Grimes chatted together all the way quite pleasantly.

They walked up a great lime avenue, a full mile long, and between their stems Tom peeped trembling at the horns of the sleeping deer, which stood up among the ferns. Tom had never seen such large trees. As he looked up he fancied that the blue sky rested on their heads. But he was puzzled very much by a strange murmuring noise, which followed them all the way. So much puzzled, that at last he took courage to ask the keeper what it was.

He spoke very civilly, and called him Sir, for he was very much afraid of him. It pleased the keeper. He told him that they were the bees about the lime flowers.

“What are bees?” asked Tom.

“What makes honey.”

“What is honey?” asked Tom.

“You hold your tongue,” said Grimes.

“Let the boy be,” said the keeper, “He’s a civil young chap now, and that’s more than he’ll be long if he bides with you.”

“I wish I were a keeper,” said Tom, “to live in such a beautiful place, and wear green velveteens, and have a real dog-whistle at my button, like you.”

The keeper laughed; he was a kind-hearted fellow enough.

By at time, they had come up to the great iron gates in front of the house Tom stared through them at the rhododendrons and azaleas, which were all in flower; and then at the house itself. He wondered how many chimneys there were in it, and how long ago it was built, and what was the man’s name that built it, and whether he got much money for his job.

But Tom and his master did not go in through the great iron gates, but round the back way. A very long way round it was; and into a little back-door, where the ash-boy let them in, yawning horribly. Then in a passage the housekeeper met them, and she gave Grimes solemn orders about, “You will take care of this, and take care of that,” as if he were going up the chimneys, and not Tom. And then the housekeeper turned them into a grand room, all covered up in sheets of brown paper, and bade them begin. So after a whimper or two, and a kick from his master, into the grate Tom went, and up the chimney, while a housemaid stayed in the room to watch the furniture.

How many chimneys Tom swept one cannot say. But he swept so many that he got quite tired, and puzzled too, for they were not like the town flues to which he was accustomed, but such as you would find in old country-houses, large and crooked chimneys, which had been altered again and again, till they ran one into another. So Tom fairly lost his way in them. But at last, coming down as he thought the right chimney, he came down the wrong one, and found himself standing on the hearthrug in a room the like of which he had never seen before.

Tom had never seen the like. He had never been in gentle folks’ rooms where the carpets were all up, and the curtains down, and the furniture huddled together under a cloth, and the pictures covered with aprons and dusters. He had often enough wondered what the rooms were like when they were all ready for the quality to sit in. Now he saw, and he thought the sight very pretty.

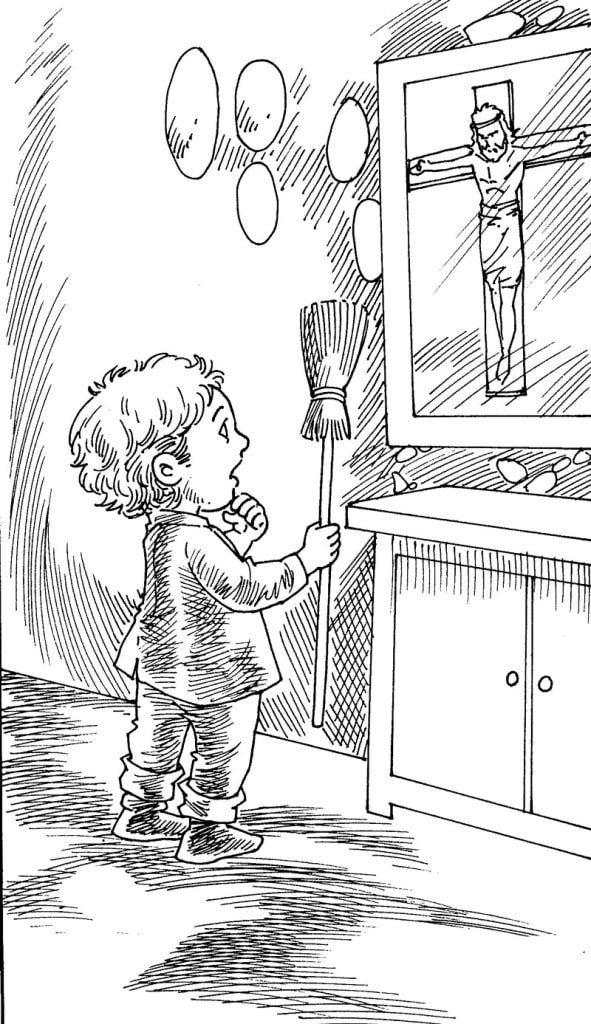

The room was all dressed in white-white window curtains, white bed-curtains, white furniture, and white walls, with just a few lines of pink here and there. The carpet was all over gay little flowers. The walls were hung with pictures in gilt frames, which amused Tom very much. There were pictures of ladies and gentlemen, and pictures of horses and dogs. But the two pictures which took his fancy most were, one a man in long garments, with little children and their mothers round him, who was laying his hand upon the children’s heads. That was a very pretty picture, Tom thought to hang in a lady’s room, for he could see that it was a lady’s room by the dresses which lay about.

The other picture was that of a man nailed to a cross, which surprised Tom much. He fancied that he had seen something like it in a shop window. But why was it there? ‘Poor man,’ thought Tom, ‘and he looks so kind and quiet. But why should the lady have such a sad picture as that in her room?’ And Tom felt sad, and awed, and turned to look at something else.

The next thing he saw, and that too puzzled him, was a washing-stand, with pewters and basins, and soap and brushes, and towels, and a large bath full of clean water. What a heap of things all for washing! ‘She must be a very dirty lady,’ thought Tom, thinking of his master, ‘to want as much scrubbing as all that. But she must be very cunning to put the dirt out of the way so well afterwards, for I don’t see a speck about the room, not even on the very towels.’

Then, looking towards the bed, he saw that dirty lady. He held his breath with astonishment.

Under the snow-white coverlet, upon the snow-white pillow, lay the most beautiful little girl that Tom had ever seen. Her cheeks were almost as white as the pillow, and her hair was like threads of gold spread all about over the bed. She might have been as old as Tom, or maybe a year or two older. But Tom did not think of that. He thought only of her delicate skin and golden hair, and wondered whether she was a real live person, or one of the wax dolls he had seen in the shops. But when he saw her breathe, he made up his mind that she was alive, and stood staring at her, as if she had been an angel out of heaven.

‘No. She cannot be dirty. She never could have been dirty,’ thought Tom to himself and then he thought, ‘Are all people like that when they are washed?’ And he looked at his own wrist, and tried to rub the soot off, and wondered whether it ever would come off. “Certainly, I should look much prettier then, if I grew at all like her.”

Looking round, he suddenly saw, standing close to him, a little ugly, black, ragged figure, with bleared eyes and grinning white teeth. He turned on it angrily. What did such a little black ape want in that sweet young lady’s room? And behold, it was himself, reflected in a great mirror, the like of which Tom had never seen before.

Tom, for the first time in his life, found out that he was dirty. He burst into tears with shame and anger; and turned to sneak up the chimney again and hide; and upset the fender and threw the fire-irons down, with a noise as of ten thousand tin kettles tied to ten thousand mad dogs’ tails.

Up jumped the little white lady in her bed. Seeing Tom, she screamed as shrill as any peacock. In rushed a stout old nurse from the next room, and seeing Tom likewise, made up her mind that he had come to rob, plunder, destroy, and burn. She dashed at him, as he lay-over the fender, so fast that she caught him by the jacket.

But she did not hold him. Tom had been in a policeman’s hands many a time, and out of them too, what is more. He would have been ashamed to face his friends for ever if he had been stupid enough to be caught by an old woman; so he doubled under the good lady’s arm, across the room, and out of the window in a moment.

He did not need to drop out, though he would have done so bravely enough. Nor even to let himself down a spout, which would have been an old game to him.

But all under the window spread a tree, with great leaves and sweet white flowers, almost as big as his head. Down the tree he went, like a cat, and across the garden lawn, and over the iron railings, and up the park towards the wood, leaving the old nurse to scream murder and fire at the window.

The undergardener, mowing, saw Tom, and threw down his scythe, and gave chase to poor Tom. The dairymaid heard the noise, got the churn between her knees, and tumbled over it, spilling all the cream. Yet, she jumped up, and gave chase to Tom. A groom cleaning Sir John’s hack at the stables let him go loose, ran out, and gave chase to Tom. Grimes upset the soot-sack in the new-gravelled yard, and spoilt it all utterly; but he ran out, and gave chase to Tom. The old steward opened the park-gate, and gave chase to Tom. The ploughman left his horses at the headland, and one jumped over the fence, and pulled the other into the ditch, plough and all; but he ran on, and gave chase to Tom. The keeper, who was taking a stoat out of a trap, let the stoat go, and caught his own finger; but he jumped up, and ran after Tom. Sir John looked out of his study window, ran out, and gave chase to Tom. The Irish woman, too, was walking up to the house to beg; but she threw away her bundle, and gave chase to Tom likewise.

In a word, never was there heard such a noise, row, hubbub, babel, shindy, hullabaloo, as that day, when Grimes, gardener, the groom, the dairymaid, Sir John, the steward, the ploughman, the keeper, and the Irish woman, all ran up the park, shouting “Stop thief,” in the belief that Tom had at least a thousand pounds’worth of jewels in his empty pockets. The very magpies and jays followed Tom up, screeching and screaming, as if he were a hunted fox.

All the while poor Tom paddled up the park with his little bare feet, like a small black gorilla fleeing to the forest.

Tom, of course, made for the woods. He had never been in a wood in his life; but he was sharp enough to know that he might hide in a bush, or swarm up a tree, and, altogether, had more chance there than in the open.

But when he got into the wood, he found it a very different sort of place from what he had fancied. He pushed into a thick cover of rhododendrons, and found himself at once caught in a trap. The boughs laid hold of his legs and arms, poked him in his face and his stomach, made him shut his eyes tight. When he got through the rhododendrons, the hassock-grass and sedges tumbled him over, and cut his poor little fingers.

‘I must get out of this,’ thought Tom, ‘or I shall stay here till somebody comes to help me—which is just what I don’t want.’

But how to get out was the difficult matter. And indeed he would ever have got out at all, if he had not suddenly run his head against a wall.

Now running your head against a wall is not pleasant, especially if it is a loose wall, with the stones all set on edge, and a sharp cornered one hits you between the eyes and makes you see all manner of beautiful stars. So, Tom hurt his head; but he was a brave boy, and did not mind that at all. He guessed that over the wall the cover would end; and up it he went, and over like a squirrel.

There he was, out on the great grousemoors, which the country folk called Harthover Fell-heather and bog and rock, stretching away and up, up to the very sky.

Now, Tom was a cunning little fellow—as cunning as an old Exmoor stag.

He knew as well as a stag that if he backed he might throw the hounds out. So the first thing he did when he was over the wall was to make the neatest double sharp to his right, and run along under the wall for nearly half a mile.

Where as Sir John, the keeper, the steward, the gardener, the ploughman, the dairymaid, and all the hue-and-cry together, went on ahead half a mile in the very opposite direction. Once inside the wall, they left him a mile off on the outside; while Tom heard their shouts die away in the woods and chuckled to himself merrily.

At last, he came to a dip in the land, and went to the bottom of it. Then he turned bravely away from the wall and up the moor, for he knew that he had put a hill between him and his enemies, and could go on without their seeing him.

But the Irish woman, alone of them all, had seen which way Tom went. She had kept ahead of everyone the whole time. Yet, she neither walked nor ran. She went along quite smoothly and gracefully, while her feet twinkled past each other so fast that you could not see which was foremost till everyone asked the other who the strange woman was.

When she came to the plantation, they lost sight of her. She went quietly over the wall after Tom, and followed him wherever he went. Sir John and the rest saw no more of her.

Now, Tom was right away into the heather. Instead of the moor growing flat as he went upwards, it grew more and more broken and hilly, but not so rough. But that little Tom could jog along well enough, and find time, too, to stare about at the strange place, which was like a new world to him.

He saw great spiders there, with crowns and crosses marked on their backs, who sat in the middle of their webs. When they saw Tom coming, they shook them so fast that they became invisible. Then he saw lizards, brown and grey and green, and thought they were snakes, and would sting him. But they were as much frightened as he, and shot away into the heath. And then, under a rock, he saw a pretty sight—a great brown, sharp-nosed creature, with a white tag to her brush, and round her four or five smutty little cubs, the funniest fellows Tom ever saw. She lay on her back, rolling about, and stretching out her legs and head and tail in the bright sunshine. The cubs jumped over her, and ran round her, and nibbled her paws, and lugged her about by the tail. She seemed to enjoy it mightily.

Next he had a fright. As he scrambled up a sandy brow-whirr-poof-poof-cock-cock-kick-something went off in his face, with a most horrid noise. He thought the ground had blown up, and the end of the world came.

When he opened his eyes (for he shut them very tight), it was only an old cock-grouse, who had been washing himself in sand. When Tom had all but trodden on him, it jumped up with a noise like the express train, and went off, screaming “Curru-u-uck, cur-ru-u-uck-murder, thieves, fire-cur-uuck-cock-kick-the end of the world has come-kick-kick-cock-kick.”

So Tom went on and on. He liked the great wide strange place, and the cool fresh bracing air. But he went more and more slowly as he got higher up the hill, for now the ground grew very bad indeed. Instead of soft turf and springy heather, he met great patches of flat limestone rock, with deep cracks between the stones and ledges, filled with ferns. So he had to hop from stone to stone. Now and then he slipped in between, and hurt his little bare toes; but still, he would go on and up.

What would Tom have said if he had seen, walking over the moor behind him, the very same Irish woman who had taken his part upon the road? But whether it was that he looked too little behind him, or whether it was that she kept out of sight behind the rocks and knolls, he never saw her, though she saw him.

Now he began to get a little hungry, and very thirsty, for he had run a long way. The sun had risen high in heaven, and the rock was as hot as an oven.

But he could see nothing to eat anywhere, and still less to drink.

The heath was full of bilberries and whim berries; but they were only in flower yet, for it was June. And as for water, who can find that on the top of a limestone rock? Now and then he passed by a deep dark swallow-hole, going down into the earth. More than once, as he passed, he could hear water falling, trickling, tinkling, many many feet below. How he longed to get down to it, and cool his poor baked lips! But, brave little chimney-sweep as he was, he dared not climb down such chimneys as those.

So he went on and on, till his head spun round with the heat. He thought he heard church bells ringing, a long way off.

‘Ah!’ he thought, ‘where there is a church there will be houses and people; and, perhaps, someone will give me a bit and a sup.’ So he set off again to look for the church, for he was sure that he heard the bells quite plain.

In a minute more, when he looked round, he stopped again and said, “Why, what a big place the world is!”

And so it was. From the top of the mountain, he could see what he could not see.

Behind him, far below, was Harthover, and the dark woods, and the shining salmon river. On his left, far below, was the town, and the smoking chimneys of the collieries. Far, far away, the river widened to the shining sea. Little white specks, which were ships, lay on its bosom. Before him lay, spread out like a map, great plains, and farms, and villages, amid dark knots of trees. They all seemed at his very feet; but he had sense to see that they were long miles away.

To his right there rose moor after moor, hill after hill, till they faded away, blue into blue sky. But between him and those moors, and really at his very feet, lay something, to which, as soon as Tom saw it, he determined to go, for that was the place for him.

There was a deep, deep green and rocky valley, very narrow, and filled with trees. But through the wood, hundreds of feet below him, he could see a clear stream glance. Oh, if he could but get down to that stream! Then, by the stream, he saw the roof of a little cottage, and a little garden set out in squares and beds. And there was a tiny little red thing moving in the garden, no bigger than a fly. As Tom looked down, he saw that it was a woman in a red petticoat. Ah! perhaps she would give him something to eat. And there were the church bells ringing again. Surely, there must be a village down there. Well, nobody would know him, or what had happened at the Place. The news could not have got there yet, even if Sir John had set all the policemen in the county after him. He could get down there in five minutes.

Tom was quite right about the hue-and-cry not having got thither; for he had come, without knowing it, the best part of ten miles from Harthover. But he was wrong about getting down in five minutes, for the cottage was more than a mile off, and a good thousand feet below.

However, down he went, like a brave little man as he was, though he was very footsore, tired, hungry and thirsty. While the church bells rang so loud, he began to think that they must be inside his own head, and the river chimed and tinkled far below.