Chapter 1

Once upon a time, there was a little chimney-sweep, and his name was Tom. He lived in a great town in the North country, where there were plenty of chimneys to sweep, and plenty of money for Tom to earn and his master to spend. He could not read nor write, and did not care to do either; and he never washed himself, for there was no water up the court where he lived. He had never been taught to say his prayers. He never had heard of God, or of Christ, except in words which you never have heard, and which it would have been well if he had never heard. He cried half his time and laughed the other half. He cried when he had to climb the dark flues, rubbing his poor knees and elbows raw; and when the soot got into his eyes, or when his master beat him, or when he had not enough to eat, which happened every day in the week. He laughed the other half of the day, when he was tossing halfpennies with the other boys, or playing leap-frog over the posts. He thought of the fine times coming, when he would be a man, and a master sweep, and sit in the public house with a quart of beer and a long pipe, and keep a white bulldog with one grey ear, and carry her puppies in his pocket, just like a man. He would have apprentices, one, two, three, if he could. How he would bully them, and knock them about, just as his master did to him; and make them carry home the soot bags, while he rode before them on his donkey, with a pipe in his mouth and a flower in his buttonhole, like a king at the head of his army.

One day, a smart little groom rode into the court where Tom lived. Tom was just hiding behind a wall to heave half a brick at his horse’s legs, when the groom saw him and halloed to him to know where Mr. Grimes, the chimney-sweep, lived. Now Mr. Grimes was Tom’s own master, so he put the half-brick down quietly behind the wall, and proceeded to take orders.

The groom said that Mr. Grimes was to come up next morning to Sir John Harthover’s, at the Place, for the chimneys wanted sweeping.

His master was so delighted at his new customer that he knocked Tom down straight away, and drank more beer that night than he usually did in two. When he got up at four the next morning, he knocked Tom down again in order to teach him that he must be an extra good boy that day, as they were going to a very great house, and might make a very good thing of it, if they could.

Tom thought so likewise, and would have behaved his best even without being knocked down.

Harthover Place was really a grand place, even for the rich North country. There were miles of game-preserves, in which Mr. Grimes and the collier lads poached at times, and a noble salmon-river, and Sir John, a grand old man, whom even Mr. Grimes respected.

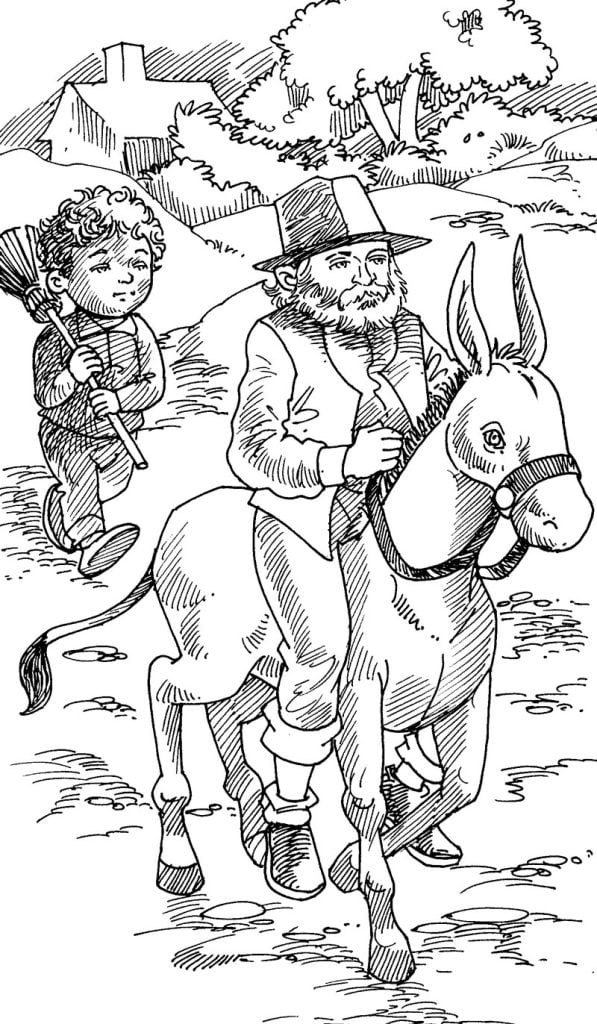

So Tom and his master set out. Grimes rode the donkey in front, and Tom and the brushes walked behind. Out of the court, and up the street, they past the closed window-shutters, and the winking weary policemen, and the roofs all shining grey in the grey dawn.

They passed through the pitmen’s village, all shut up and silent now. Then they were out in the real country, and plodding along the black dusty road, between black slag walls, with no sound but the groaning and thumping of the pit-engine in the next field. But soon the road grew white, and the walls likewise. At the wall’s foot grew long grass and gay flowers, all drenched with dew. Instead of the groaning of the pit-engine, they heard the skylark saying his matins high up in the air, and the pit-bird warbling in the sedges, as he had warbled all night long.

All else was silent, for old Mrs. Earth was still fast asleep. Like many pretty people, she looked still prettier asleep than awake. The great elm-trees in the gold-green meadows were fast asleep above, and the cows fast asleep beneath them; nay the few clouds which were fast asleep likewise. So tired they were that they had lain down on the earth to rest, in long white flakes and bars, among the stems of the elm-trees, and along the tops of the alders by the stream, waiting for the sun to bid them rise and go about their day’s business in the clear blue overhead.

On they went. Tom looked and looked, for he never had been so far into the country before. He longed to get over a gate, and pick buttercups, and look for birds’ nests in the hedge. But Mr. Grimes was a man of business, and would not have heard of that.

Soon they came up with a poor Irish woman, trudging along with a bundle at her back. She had a grey shawl over her head, and a crimson petticoat. She had neither shoes nor stockings, and limped along as if she were tired and footsore. But she was a very tall handsome woman, with bright grey eyes, and heavy black hair hanging about her cheeks. She took Mr. Grimes’ fancy so much, that when he came alongside he called out to her, “This is a hard road; will you, lass, ride behind me?”

But perhaps, she did not like Mr. Grimes’ look and voice; for she answered quietly, “No, thank you, I’d sooner walk with your little lad here.”

“You may please yourself,” growled Grimes, and went on smoking.

So she walked beside Tom, and talked to him, and asked him where he lived, and what he knew, and all about himself. Tom thought he had never met such a pleasant-spoken woman. She asked him, at last, whether he said his prayers. She seemed sad when he told her that he knew no prayers to say.

Then he asked her where she lived. She said that she lived far away by the sea. Tom asked her about the sea; and she told him how it rolled and roared over the rocks in winter nights, and lay still in the bright summer days, for the children to bathe and play in it. Many a story more, till Tom longed to go and see the sea, and bathe in it likewise.

At last, at the bottom of a hill, they came to a spring. Out of a low cave of rock, at the foot of a limestone crag, the great fountain rose, and ran away under the road, a stream large enough to turn a mill.

There, Grimes stopped, and looked; and Tom looked too. Tom was wondering whether anything lived in that dark cave, and came out at night to fly in the meadows. But Grimes was not wondering at all. Without a word, he got off his donkey, and clambered over the low road wall, and knelt down, and began dipping his ugly head into the spring. He made it very dirty.

Tom was picking him the flowers as fast as he could. The Irishwoman helped him, and showed him how to tie them up. A very pretty nosegay they had made between them. But when he saw Grimes actually wash, he stopped, quite astonished. When Grimes had finished, and began shaking his ears to dry them, he said, “Why, master, I never saw you do that before.”

“Nor will again, most likely. It wasn’t for cleanliness I did it, but for coolness.”

“I wish I might go and dip my head in,” said poor little Tom.

“You come along,” said Grimes, “What do you want with washing yourself? You did not drink half a gallon of beer last night, like me.”

“I don’t care for you,” said naughty Tom, and ran down to the stream, and began washing his face.

Grimes was very sulky, because the woman preferred Tom’s company to his; so he dashed at him with horrid words, and tore him up from his knees, and began beating him. But Tom was used to that, and got his head safe between Mr. Grimes’ legs, and kicked his shins with all his might.

“Are you not ashamed of yourself, Thomas Grimes?” cried the Irishwoman over the wall.

Grimes looked up, startled at her knowing his name; but all he answered was, “No, nor never was yet;” and went on beating Tom.

“True for you. If you ever had been ashamed of your- self, you would have gone over into Vendale long ago.”

“What do you know about Vendale?” shouted Grimes. Thus he left off beating Tom.

“I know about Vendale, and about you, too. I know, for instance, what happened by night two years ago.”

“You do?” shouted Grimes. Leaving Tom, he climbed up over the wall, and faced the woman. Tom thought he was going to strike her; but she looked him too full and fierce in the face for that.

“Yes; I was there,” said the Irish woman quietly.

“You are no Irish woman, by your speech,” said Grimes, after many bad words.

“Never mind who I am. I saw what I saw; and if you strike that boy again, I can tell what I know.”

Grimes seemed quite cowed, and got on his donkey without another word.

“Stop!” said the Irishwoman, “I have one more word for you both; for you will both see me again before all is over. Those that wish to be clean, clean they will be; and those that wish to be foul, foul they will be. Remember.”

She turned away, and through a gate into the meadow. Grimes stood still a moment, like a man who had been stunned. Then he rushed after her, shouting, “You come back.” But when he got into the meadow, the woman was not there.

Had she hidden away? There was no place to hide in. But Grimes looked about, and Tom also, for he was as puzzled as Grimes himself at her disappearance so suddenly. But she was not there.

Grimes came back again, as silent as a post, for he was a little frightened. Getting on his donkey, he filled a fresh pipe, and smoked away, leaving Tom in peace.