Chapter 10

When Marguerite reached her room, she found her maid terribly anxious about her.

“Your ladyship will be so tired,” said the poor woman, whose own eyes were half closed with sleep. “It is past five o’clock.”

“Ah, yes, Louise, I daresay I shall be tired presently,” said Marguerite, kindly; “but you are very tired now, so go to bed at once. I’ll get into bed alone.”

“But, my lady.”

“Now, don’t argue, Louise, but go to bed. Give me a wrap, and leave me alone.”

Louise was only too glad to obey. She took off her mistress’s gorgeous ball-dress, and wrapped her up in a soft billowy gown.

“Does your ladyship wish for anything else?” she asked, when that was done.

“No, nothing more. Put out the lights as you go out.”

“Yes, my lady. Good-night, my lady.”

“Good-night, Louise.”

When the maid was gone, Marguerite drew aside the curtains and threw open the windows. The garden and the river beyond were flooded with rosy light. Far away to the east, the rays of the rising sun had changed the rose into vivid gold. The lawn was deserted now, and Marguerite looked down upon the terrace where she had stood a few moments ago trying in vain to win back a man’s love, which once had been so wholly hers.

It was strange that through all her troubles, all her anxiety for Armand, she was mostly conscious at the present moment of a keen and bitter heartache.

Her very limbs seemed to ache with longing for the love of a man who had spurned her, who had resisted her tenderness, remained cold to her appeals, and had not responded to the glow of passion, which had caused her to feel and hope that those happy olden days in Paris were not all dead and forgotten.

A woman’s heart is such a complex problem—the owner thereof is often most incompetent to find the solution of this puzzle.

Thus the most contradictory thoughts and emotions rushed madly through her mind. Absorbed in them, she had allowed time to slip by; perhaps, tired out with long excitement, she had actually closed her eyes and sunk into a troubled sleep, wherein quickly fleeting dreams seemed but the continuation of her anxious thoughts—when suddenly she was roused, from dream or meditation, by the noise of footsteps outside her door.

Nervously she jumped up and listened; the house itself was as still as ever; the footsteps had retreated. Through her wide-open window the brilliant rays of the morning sun were flooding her room with light. She looked up at the clock; it was half-past six—too early for any of the household to be already astir.

She certainly must have dropped asleep, quite unconsciously. The noise of the footsteps, also of hushed subdued voices had awakened her—what could they be?

At last she stooped to pick it up, and, amazed, puzzled beyond measure, she saw that the letter was addressed to herself in her husband’s large, businesslike-looking hand. What could he have to say to her, in the middle of the night, which could not be put off until the morning?

She tore open the envelope and read:—

“A most unforeseen circumstance forces me to leave for the North immediately, so I beg your ladyship’s pardon if I do not avail myself of the honour of bidding you good-bye. My business may keep me employed for about a week, so I shall not have the privilege of being present at your ladyship’s water-party on Wednesday. I remain your ladyship’s most humble and most obedient servant, PERCY BLAKENEY.”

Marguerite must suddenly have been imbued with her husband’s slowness of intellect, for she had perforce to read the few simple lines over and over again, before she could fully grasp their meaning.

She stood on the landing, turning over and over in her hand this curt and mysterious epistle, her mind a blank, her nerves strained with agitation and a presentiment she could not very well have explained.

Sir Percy owned considerable property in the North, certainly, and he had often before gone there alone and stayed away a week at a time; but it seemed so very strange that circumstances should have arisen between five and six o’clock in the morning that compelled him to start in this extreme hurry.

Vainly she tried to shake off an unaccustomed feeling of nervousness: she was trembling from head to foot. A wild, unconquerable desire seized her to see her husband again, at once, if only he had not already started.

Forgetting the fact that she was only very lightly clad in a morning wrap, and that her hair lay loosely about her shoulders, she flew down the stairs, right through the hall towards the front door.

It was as usual barred and bolted, for the indoor servants were not yet up; but her keen ears had detected the sound of voices and the pawing of a horse’s hoof against the flag-stones.

With nervous, trembling fingers Marguerite undid the bolts one by one, bruising her hands, hurting her nails, for the locks were heavy and stiff. But she did not care; her whole frame shook with anxiety at the very thought that she might be too late; that he might have gone without her seeing him and bidding him “God-speed!”

At last, she had turned the key and thrown open the door. Her ears had not deceived her. A groom was standing close by holding a couple of horses; one of these was Sultan, Sir Percy’s favourite and swiftest horse, saddled ready for a journey.

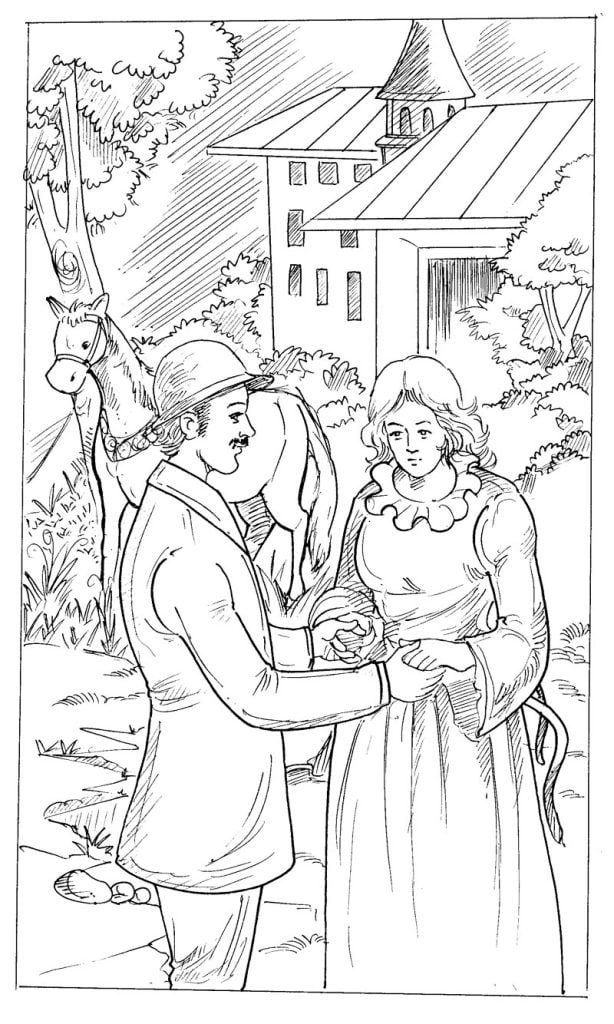

The next moment Sir Percy himself appeared round the further corner of the house and came quickly towards the horses. He had changed his gorgeous ball costume, but was as usual irreproachably and richly apparelled in a suit of fine cloth, with lace jabot and ruffles, high top-boots, and riding breeches.

Marguerite went forward a few steps. He looked up and saw her. A slight frown appeared between his eyes.

“You are going?” she said quickly and feverishly. “Whither?”

“As I have had the honour of informing your ladyship, urgent, most unexpected business calls me to the North this morning,” he said, in his usual cold, drawly manner.

“But your guests to-morrow.”

“I have prayed your ladyship to offer my humble excuses to His Royal Highness. You are such a perfect hostess, I do not think I shall be missed.”

“But surely you might have waited for your journey until after our water-party,” she said, still speaking quickly and nervously. “Surely this business is not so urgent and you said nothing about it—just now.”

“My business, as I had the honour to tell you, Madame, is as unexpected as it is urgent. May I therefore crave your permission to go? Can I do aught for you in town?”

“No, no; thanks. Nothing. But you will be back soon?”

“Very soon.”

“Before the end of the week?”

“I cannot say.”

He was evidently trying to get away, whilst she was straining every nerve to keep him back for a moment or two.

“Nay, there is no mystery, Madame,” he replied, with a slight tone of impatience. “My business has to do with Armand. . .there! Now, have I your leave to depart?”

“With Armand? But you will run no danger?”

“Danger? I? Nay, Madame, your solicitude does me honour. As you say, I have some influence; my intention is to exert it before it be too late.”

“Will you allow me to thank you at least?”

“Nay, Madame,” he said coldly, “there is no need for that. My life is at your service, and I am already more than repaid.”

“And mine will be at yours, Sir Percy, if you will but accept it, in exchange for what you do for Armand,” she said, as, impulsively, she stretched out both her hands to him. “There! I will not detain you. My thoughts go with you. Farewell!”

How lovely she looked in this morning sunlight, with her ardent hair streaming around her shoulders. He bowed very low and kissed her hand; she felt the burning kiss and her heart thrilled with joy and hope.

“You will come back?” she said tenderly.

“Very soon!” he replied, looking longingly into her blue eyes.

“Any; you will remember?” she asked as her eyes, in response to his look, gave him an infinity of promise.

“I will always remember, Madame, that you have honoured me by commanding my services.”

The words were cold and formal, but they did not chill her this time. Her woman’s heart had read his, beneath the impassive mask his pride still forced him to wear.

He bowed to her again, then begged her leave to depart. She stood on one side whilst he jumped on to Sultan’s back, then, as he galloped out of the gates, she waved him a final ‘adieu.’

Her heart seemed all at once to be in complete peace, and, though it still ached with undefined longing, a vague and delicious hope soothed it as with a balm.

She felt no longer anxious about Armand. The man who had just ridden away, bent on helping her brother, inspired her with complete confidence in his strength and in his power. She marvelled at herself for having ever looked upon him as an inane fool; of course, THAT was a mask worn to hide the bitter wound she had dealt to his faith and to his love. His passion would have overmastered him, and he would not let her see how much he still cared and how deeply he suffered.

But now all would be well: she would crush her own pride, humble it before him, tell him everything, trust him in everything; and those happy days would come back, when they used to wander off together in the forests of Fontainebleau, when they spoke little—for he was always a silent man—but when she felt that against that strong heart she would always find rest and happiness.

The more she thought of the events of the past night, the less fear had she of Chauvelin and his schemes. He had failed to discover the identity of the Scarlet Pimpernel, of that she felt sure. Both Lord Fancourt and Chauvelin himself had assured her that no one had been in the dining-room at one o’clock except the Frenchman himself and Percy—Yes!—Percy! she might have asked him, had she thought of it! Anyway, she had no fears that the unknown and brave hero would fall in Chauvelin’s trap; his death at any rate would not be at her door.

The day was well advanced when Marguerite woke, refreshed by her long sleep. Louise had brought her some fresh milk and a dish of fruit, and she partook of this frugal breakfast with hearty appetite.

Thoughts crowded thick and fast in her mind as she munched her grapes; most of them went galloping away after the tall, erect figure of her husband, whom she had watched riding out of site more than five hours ago.

In answer to her eager inquiries, Louise brought back the news that the groom had come home with Sultan, having left Sir Percy in London. The groom thought that his master was about to get on board his schooner, which was lying off just below London Bridge. Sir Percy had ridden thus far, had then met Briggs, the skipper of the DAY DREAM, and had sent the groom back to Richmond with Sultan and the empty saddle.

Marguerite expected her eagerly; she longed for a chat about old schooldays with the child; she felt that she would prefer Suzanne’s company to that of anyone else, and together they would roam through the fine old garden and rich deer park, or stroll along the river.

But Suzanne had not come yet, and Marguerite being dressed, prepared to go downstairs. She looked quite a girl this morning in her simple muslin frock, with a broad blue sash round her slim waist, and the dainty cross-over fichu into which, at her bosom, she had fastened a few late crimson roses.

She crossed the landing outside her own suite of apartments, and stood still for a moment at the head of the fine oak staircase, which led to the lower floor. On her left were her husband’s apartments, a suite of rooms which she practically never entered.

They consisted of bedroom, dressing and reception room, and at the extreme end of the landing, of a small study, which, when Sir Percy did not use it, was always kept locked. His own special and confidential valet, Frank, had charge of this room. No one was ever allowed to go inside. My lady had never cared to do so, and the other servants, had, of course, not dared to break this hard-and-fast rule.

Marguerite thought of all this on this bright October morning as she glanced along the corridor. Frank was evidently busy with his master’s rooms, for most of the doors stood open, that of the study amongst the others.

Gently, on tip-toe, she crossed the landing and, like Blue Beard’s wife, trembling half with excitement and wonder, she paused a moment on the threshold, strangely perturbed and irresolute.

The door was ajar, and she could not see anything within. She pushed it open tentatively: there was no sound: Frank was evidently not there, and she walked boldly in.

At once she was struck by the severe simplicity of everything around her: the dark and heavy hangings, the massive oak furniture, the one or two maps on the wall, in no way recalled to her mind the lazy man about town, the lover of race-courses, the dandified leader of fashion, that was the outward representation of Sir Percy Blakeney.

There was no sign here, at any rate, of hurried departure. Everything was in its place, not a scrap of paper littered the floor, not a cupboard or drawer was left open. The curtains were drawn aside, and through the open window the fresh morning air was streaming in.

Facing the window, and well into the centre of the room, stood a ponderous business-like desk, which looked as if it had seen much service. On the wall to the left of the desk, reaching almost from floor to ceiling, was a large full-length portrait of a woman, magnificently framed, exquisitely painted, and signed with the name of Boucher. It was Percy’s mother.

Marguerite studied the portrait, for it interested her: after that she turned and looked again at the ponderous desk. It was covered with a mass of papers, all neatly tied and docketed, which looked like accounts and receipts arrayed with perfect method. It had never before struck Marguerite—nor had she, alas! found it worth while to inquire—as to how Sir Percy, whom all the world had credited with a total lack of brains, administered the vast fortune which his father had left him.

Since she had entered this neat, orderly room, she had been taken so much by surprise, that this obvious proof of her husband’s strong business capacities did not cause her more than a passing thought of wonder. But it also strengthened her in the now certain knowledge that, with his worldly inanities, his foppish ways, and foolish talk, he was not only wearing a mask, but was playing a deliberate and studied part.

Marguerite wondered again. Why should he take all this trouble? Why should he—who was obviously a serious, earnest man—wish to appear before his fellow-men as an empty-headed nincompoop?

He may have wished to hide his love for a wife who held him in contempt but surely such an object could have been gained at less sacrifice, and with far less trouble than constant incessant acting of an unnatural part.

She looked round her quite aimlessly now: she was horribly puzzled, and a nameless dread, before all this strange, unaccountable mystery, had begun to seize upon her. She felt cold and uncomfortable suddenly in this severe and dark room. There were no pictures on the wall, save the fine Boucher portrait, only a couple of maps, both of parts of France, one of the North coast and the other of the environs of Paris. What did Sir Percy want with those, she wondered.

Her head began to ache, she turned away from this strange Blue Beard’s chamber, which she had entered, and which she did not understand. She did not wish Frank to find her here, and with a fast look round, she once more turned to the door. As she did so, her foot knocked against a small object, which had apparently been lying close to the desk, on the carpet, and which now went rolling, right across the room.

She stooped to pick it up. It was a solid gold ring, with a flat shield, on which was engraved a small device.

Marguerite turned it over in her fingers, and then studied the engraving on the shield. It represented a small star-shaped flower, of a shape she had seen so distinctly twice before: once at the opera, and once at Lord Grenville’s ball.

❒