Chapter 12

It was now harvest, and our crop in good order. It was not the most plentiful increase I had seen in the island, but however, it was enough to answer our end; for from our twenty-two bushels of barley we brought in and thrashed out above two hundred and twenty bushels, and the like in proportion of the rice; which was store enough for our food to the next harvest, though all the sixteen Spaniards had been on shore with me; or if we had been ready for a voyage, it would very plentifully have victualled our ship.

When we had thus housed and secured our magazine of corn, we fell to work to make more wicker-work, namely, great baskets in which we kept it; and the Spaniard was very handy and dexterous at this part, and often blamed me that I did not make some things for defence of this kind of work; but I saw no need of it.

And now having a full supply of food for all the guests I expected, I gave the Spaniard leave to go over to the main to see what he could do with those he had left behind him there.

Under these instructions, the Spaniard and the old savage, the father of Friday, went away in one of the canoes. I gave each of them a musket and a firelock on it, and about eight charges of powder and ball, charging them to be very good husbands of both, and not use either of them but upon urgent occasion.

It was no less than eight days I waited for them when a strange and unforeseen accident intervened. I was fast asleep in my hutch one morning, when my man Friday came running in to me and called aloud, “Master, master, they are come, they are come!”

I jumped up, and regardless of danger, I went without my arms, which was not my custom to do; but I was surprised, when, turning my eyes to the sea, I presently saw a boat at about a league and a half’s distance, standing in for the shore with a shoulder-of-mutton sail, as they call it; and the wind blowing pretty fair to bring them in. Upon this I called Friday in, and bade him lie close, for these were not the people we looked for, and that we might not know yet whether they were friends or enemies.

In the next place, I went in to fetch my perspective-glass to see what I could make of them; and having taken the ladder out, I climbed up to the top of the hill.

I had scarce set my foot on the hill, when my eye plainly discovered a ship lying at an anchor, at about two leagues and a half’s distance from me south-south-east, but not above a league and a half from the shore. By my observation it appeared plainly to be an English ship, and the boat appeared to be an English long-boat.

I had not kept myself long in this posture, but I saw the boat draw near the shore, as if they looked for a creek to thrust in at for the convenience of landing. However, as they did not come quite far enough, they did not see the little inlet where I formerly landed my rafts, but run their boat on shore upon the beach, at about half a mile from me.

When they were on shore, I was fully satisfied that they were Englishmen, at least most of them. They were in all eleven men, whereof three of them I found were unarmed, and, as I thought, bound; and when the first four or five of them had jumped on shore, they took these three out of the boat as prisoners.

I had no thought of what the matter really was, but stood trembling with the horror of the sight, expecting every moment when the three prisoners should be killed; nay, once I saw one of the villains lift up his arm with a great cutlass, as the seamen call it, or sword, to strike one of the poor men.

After I had observed the outrageous usage of the three men by the insolent seamen, I observed the fellows run scattering about the land, as if they wanted to see the country. I observed that the three other men had liberty to go also where they pleased; but they sat down all three upon the ground, very pensive, and looked like men in despair.

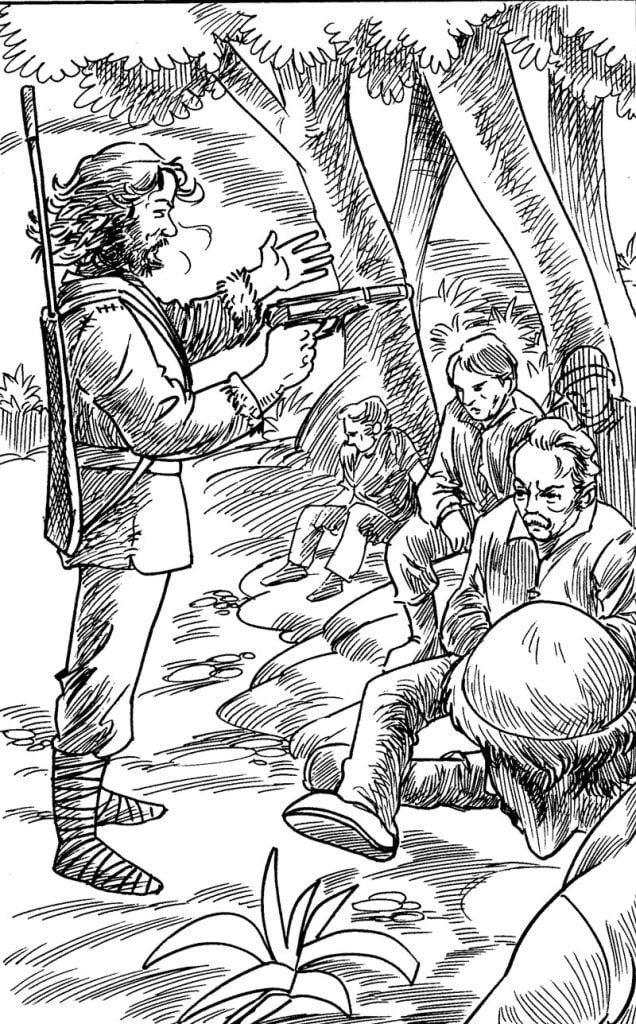

Upon this I resolved to discover myself to them, and learn something of their condition. I came as near them undiscovered as I could, and then, before any of them saw me, I called aloud to them in Spanish, “What are you, gentlemen?”

They started up at the noise, but were ten times more confounded when they saw me, and the uncouth figure that I made. They made no answer at all, but I thought I perceived them just going to fly from me, when I spoke to them in English. “Gentlemen,” said I, “do not be surprised at me; perhaps you may have a friend near you when you did not expect it.”

“Our case,” said one, “sir, is too long to tell you while our murderers are so near; but in short, sir, I was commander of that ship; my men have mutinied against me; they have been hardly prevailed on not to murder me, and in last have set me on shore in this desolate place, with these two men with me; one my mate, the other a passenger.”

“Look you, sir,” said I, “if I venture your deliverance, are you willing to make two conditions with me?” He anticipated my proposals by telling me that both he and the ship, if recovered, should be wholly directed and commanded by me in everything.

“Well,” say I, “my conditions are but two: I. That while you stay on this island with me you will not pretend to any authority here. 2. That if the ship is, or may be recovered, you will carry me and my man to England passage free.”

He gave me all the assurances that the invention and faith of man could devise, that he would comply with these most reasonable demands, and besides would owe his life to me, and he acknowledged it upon all occasions as long as he lived.

“Well, then,” said I, “here are three muskets for you, with powder and ball; tell me next what you think is proper to be done.”

He said very modestly, that he had loathed to kill them if he could help it, but that two were incorrigible villains, and had been the authors of all the mutiny in the ship, and if they escaped we should be undone still; for they would go on board and bring the whole ships company, and destroy us all.

Animated, he took the musket I had given him in his hand, and a pistol in his belt, and his two comrades with him, with each man a piece in his hand. The two men who were with him, going first made some noise, at which one of the seamen who was awake turned about, and seeing them coming, cried out to the rest. But it was too late then; for the moment he cried out they fired. They had so well aimed their shot at the men they knew, that one of them was killed on the spot, and the other very much wounded; but not being dead, he started up upon his feet, and called eagerly for help to the other; but the captain, stepping to him, told him it was too late to cry for help, he should call upon God to forgive his villany, and with that word knocked him down with the stock of his musket, so that he never spoke more. They were three more in the company, and one of them was also slightly wounded. By this time I had come, and when they saw their danger, and that it was in vain to resist, they begged for mercy. The captain told them he would spare their lives, which I was not against; only I obliged him to keep them bound hand and foot while they were upon the island.

While this was doing, I sent Friday with the captain’s mate to the boat, with orders to secure her and bring away the oars and sail; which they did. And by and by, three straggling men, that were (happily for them) parted from the rest, came back upon hearing the guns fired; and seeing their captain, who before was their prisoner, they submitted to be bound also, and so our victory was complete.

It now remained that the captain and I should consider how to recover the ship. He told me he was perfectly at a loss what measures to take; for that there were still six-and-twenty hands on board, who, having entered into a cursed conspiracy, by which they had all forfeited their lives to the law, would be hardened in it now by desperation.

Upon this it presently occurred to me that in a little while the ship’s crew, wondering what had become of their comrades and of the boat, would certainly come on shore in their other boat to see for them. I told him the first thing we had to do was to stave that boat which lay upon the beach, so that they might not carry her off; and taking everything out of her, leave her so far useless as not to be fit to swim. Accordingly, we went on board, took the arms which were left on board out of her, and whatever else we found there, then we knocked a great hole in her bottom, that if they had come strong enough to master us, yet they could not carry off the boat.

While we heaved the boat up upon the beach, so high that the tide would not float her off at high water mark; and besides, had broken a hole in her bottom too big to be quickly stopped, we heard the ship fire a gun.

At last, when all their signals and firings proved fruitless, and they found the boat did not stir, we saw them, by the help of my glasses, hoist another boat out, and row towards the shore; and we found as they approached that there was no less than ten men in her, and that they had firearms with them.

Seven men came on shore and the three who remained in the boat put her off to a good distance from the shore, and came to an anchor to wait for them; so that it was impossible for us to come at them in the boat.

Those that came on shore kept close together, marching towards the top of the little hill under which my habitation lay; and we could see them plainly, though they could not perceive us.

We waited a great while, though very impatient for their removing; and were very uneasy when, after long consultations, we saw them start all up and march down towards the sea.

As soon as I perceived them go towards the shore, I ordered Friday and the captain’s mate to go over the little creek westward, towards the place where the savages came on shore when Friday was rescued; and as soon as they came to a little rising ground, at about half a mile distance, I bade them halloo as loud as they could, and wait till they found the seamen heard them; that as soon as ever they heard the seamen answer them they should return it again; and then, keeping out of sight, take a round, always answering when the other hallooed, to draw them as far into the island, and among the woods, as possible, and then wheel about again to me by such ways as I directed them.

They were just going into the boat when Friday and the mate hallooed; and they presently heard them, and answering, run along the shore westward, towards the voice they heard, when they were presently stopped by the creek, where the water being up, they could not get over, and called for the boat to come up and set them over, as indeed I expected.

When they had set themselves over, I observed that the boat, being gone up a good way into the creek, and, as it were, in a harbour within the land, they took one of the three men out of her to go along with them, and left only two in the boat, having fastened her to the stump of a little tree on the shore.

This was what I wished for, and immediately leaving Friday and the captain’s mate to their business, I took the rest with me, and crossing the creek out of their sight, we surprised the two men before they were aware; one of them lying on shore, and the other being in the boat. The fellow on shore was between sleeping and waking, and going to start up, the captain, who was foremost, ran in upon him, and knocked him down, and then called out to him in the boat to yield, or he was a dead man.

There needed very few arguments to persuade a single man to yield when he saw five men upon him, and his comrade knocked down; besides, this was, it seemed, one of the three who were not so hearty in the mutiny as the rest of the crew, and therefore, was easily persuaded not only to yield, but afterwards to join very sincerely with us.

In the meantime Friday and the captain’s mate so well managed their business with the rest, that they drew them, by hallowing and answering, from one hill to another, and from one wood to another, till they not only heartily tired them, but left them where they were very sure they could not reach back to the boat before it was dark; and indeed they were heartily tired themselves also by the time they came back to us.

We had nothing now to do but to watch for them in the dark, and to fall upon them, so as to make sure work with them.

It was several hours after Friday had come back to me before they came back to their boat; and we could hear the foremost of them long before…they came quite up, calling to those behind to come along; and could also hear them answer and complain how lame and tired they were, and not able to come any faster—which was very welcome news to us.

At length they came up to the boat; but it was impossible to express their confusion when they found the boat fast aground in the creek, the tide ebbed out, and their two men gone!

My men would fain have me give them leave to fall upon them at once in the dark; but I was willing to take them at some advantage so to spare them, and kill as few of them as I could; and especially I was unwilling to hazard the killing any of our own men, knowing the other were very well armed. But when they came nearer, the captain and Friday starting up on their feet, let fly at them.

The boatswain was killed upon the spot, the next man was shot into the body, and fell just by him, and the third run for it.

At the noise of the fire I immediately advanced with my whole army, which was now eight men, namely, myself generalissimo, Friday my lieutenant-general, the captain and his two men, and the three prisoners of war, who we had trusted with arms.

So taken by surprise were they that they all laid down their arms, and begged their lives; and then my great army of eight men, came up and seized upon them all, and upon their boat—only that I kept myself and one more out of sight, for reasons of state.

Our next work was to repair the boat, and think of seizing the ship; and as for the captain, now he had leisure to parley with them, he expostulated with them upon the villany of their practices with him, and at length upon the farther wickedness of their design, and how certainly it must bring them to misery and distress in the end, and perhaps to the gallows.

I asked the captain if he was willing to venture on board the ship; for as for me and my man Friday, I did not think it was proper for us to stir, having seven men left behind, and it was employment enough for us to keep them asunder and supply them with their victuals.

The captain had no difficulty before him but to furnish his two boats, stop the breach of one and man them. He made his passenger captain of one, with four other men; and himself, and his mate and five men, went in the other. And they continued to contrive their business very well, for they came up to the ship about midnight, and the ship was taken effectually, with few lives lost.