In early 1918, the crops of Kaira district were washed away by rain. The farmers were left with nothing and could not pay the land revenue. They prayed for the exemption of land tax. But the government turned a deaf ear to their request. So the people approached Vallabhbhai for help. Vallabhbhai himself visited the villages on a fact-finding inquiring and when he was satisfied he wrote to the government of Bombay to grant exemption from land revenue. But this had no effect. So Vallabhbhai approached Gandhiji to take up the case of the Kaira peasants. Gandhiji advised satyagraha but he wanted “one at least of the workers of Gujarat Sabha to accompany him and devote all his time to the campaign until it was completed”.

Vallabhbhai offered his services, much to Gandhiji’s delight. For Vallabhbhai, the Kaira Satyagraha was only the beginning in a series of political involvement designed to align him to Gandhiji and to that section that could and would follow Gandhiji. He discarded his English dress from February 1918 onwards and the dhoti- kurta now became for him the symbols of his new alignment and strategy.

Vallabhbhai toured the villages of Kaira district along with Gandhiji to train the people to suffer in the cause of Satyagraha. When Gandhiji appealed to the people to refrain from paying land revenue, the government became furious and enforced punitive measures for tax collections. Lands were attached, property confiscated, and cattle were auctioned. This meant too great a hardship for the famine-hit people of Kaira. Gandhiji had to leave Kaira to go to Champaran in Bihar and made Vallabhbhai in charge.

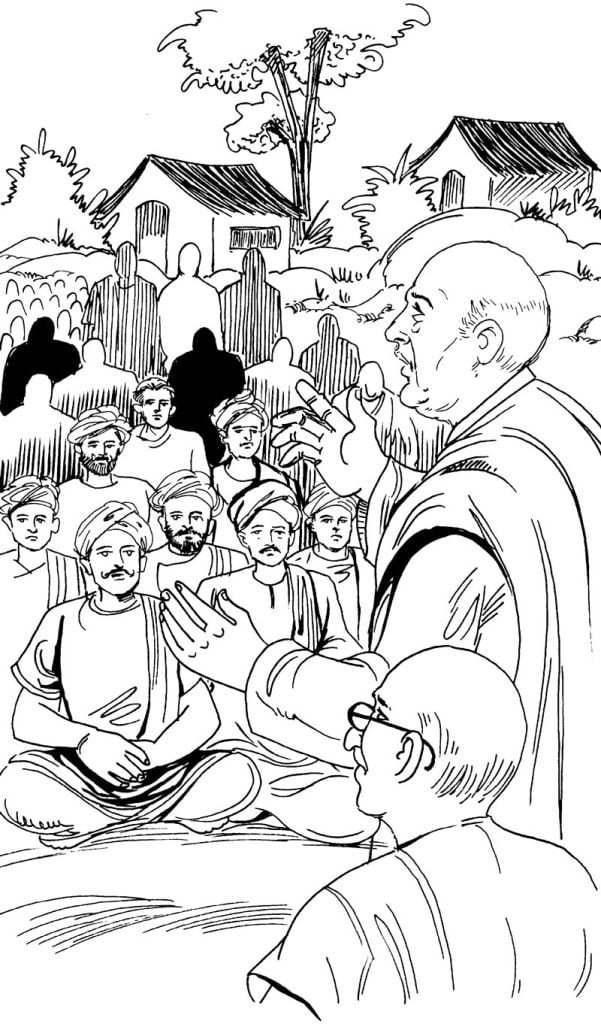

At a meeting presided by Vallabhbhai at Nadiad on 31st March, farmers pledged their full support and were even willing to face the consequences of attachment. Vallabhbhai visited may villages including Uttarsanda, Chakhari, Bhainal and Golel and at well attended meetings commended the courage of the farmers while warning them of the hardships to come in time. Leaders of villages commended Vallabhbhai’s own sacrifice of his professional interests and his keen interest in peasant affairs.

The presence of Patidar district pleader who had come to their native villages from Ahmedabad to help in the campaign gave further impetus to the movement. Vallabhbhai’s presence created particular enthusiasm and in Borsad, where the Patel’s brothers were well-known, farmers took them in a procession and paid them glowing tributes. By April 4, about 1500 people had signed a petition to the government which gave added publicity and strength to the campaign. Commending Patel’s efforts Gandhiji, said at Karamsad in April 1918—

“This is Vallabhbhai’s native place. Vallabhbhai is still in the fire and will have to endure a good deal of heat, but I think out of all this; we shall have gold in the end. Let your wishes go with him.”

Ultimately the government had to yield. It agreed that the tax should be collected only from those who could pay it. This was what the Gujarat Sabha had been asking for. So the no-tax campaign was called off.

The Kaira Satyagraha is of particular significance not merely because it marked the beginning of Vallabhbhai’s improvement in active politics but also because it gave him a political power base. As a result of his method of functioning, he linked Gujarat Sabha to the Congress Party in a manner which he himself could use to his and the party’s advantage. He worked in Kaira and other Gujarat areas with a view to making them future reservoirs of support for Congress. His Patidar background, the experience in rural Gujarat, his capacity and eagerness for political advancement made Vallabhbhai an asset and deputy general to Gandhiji. Gandhiji said in a speech—

“I wondered who the deputy general should be. My eye fell on Vallabhbhai. I must admit that the first time I saw him I wondered who that stiff man could be. What could he do! But as I came in contact with him I knew that I must have him.”

Soon after the successful completion of the Kaira Satyagraha, Vallabhbhai joined Gandhiji in raising recruits for the war which was going on at that time. But once the war was over “victory brought a certain racial arrogance, accentuating the worst features of the British occupation…No European showed any recognition of the political and social changes of the war period. It was treated as a mere interlude, and the chief anxiety was to resuscitate the old Anglo-India life”.

As if to add fuel to the fire the Rawlett Committee’s report was published. It wrecommended the passing of two bills. One of the Bill provided for the trials without right of appeal by special courts in camera for demanding security from persons liking to commit offenses, and for the arrests on mere suspicion. The other bill was intended to introduce permanent changes in the ordinary criminal law and to make even the possession of a seditious document punishable with two year’s imprisonment. It was a great blow to individual liberty. Naturally there was a lot of resentment over these bills. Vallabhbhai said—“During the war we were told by the government that if we helped them in the war effort we should be granted freedom after the war…the war is over. Instead of improvements in the administration in recognition of our help we have been given the Rawlett Bills. This kind of law does not exist in any part of the world.”

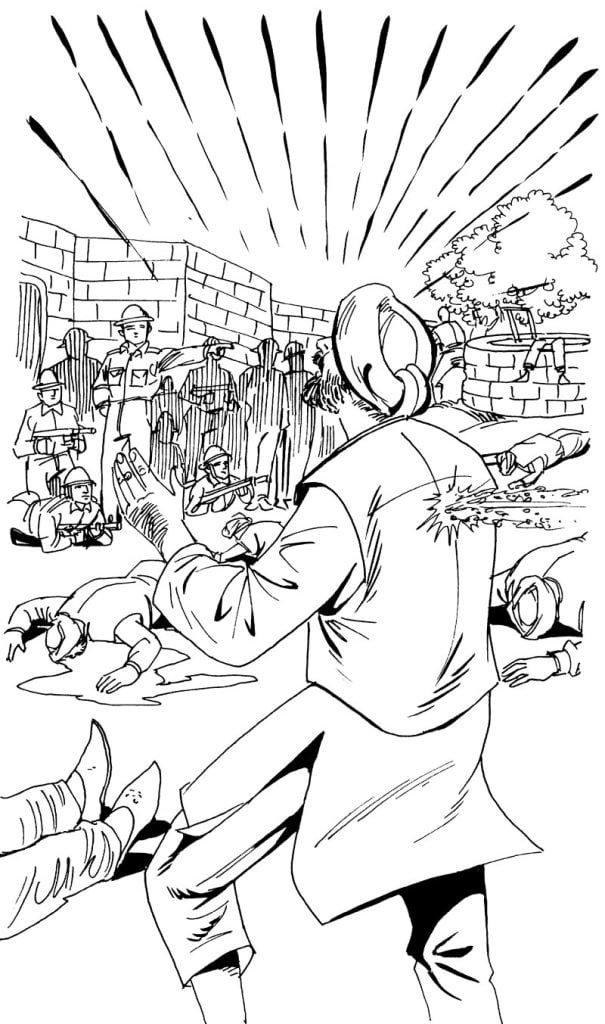

After the Rawlett Bill came the massacre of Jallianwala Bagh. April 13th 1919, was a Sunday and the day of Baisakhi. To celebrate this festival thousands of people had come from the neighbouring villages. In the evening about 20,000 people had gathered at Jallianwala Bagh to attend a public meeting which was held to protest against the unjust Rawlett Bills passed by the government and the arrests of two local leaders, Dr. Kichlew and Dr. Satpal.

The Lt. Governor of Pubjab at that time was Michael O’ Dwyer who believed in force. And to teach the people of Amritsar a lesson he had called the army to take control of the situation. General Dyer was in command of the army. When General Dyer learnt about the meeting he immediately rushed to the spot and closed the only narrow exit and without any warning started firing on the peaceful crowd. The firing went on for 10 minutes and stopped only when ammunition was exhausted. In all, 1650 rounds were fired. Even according to a very moderate estimate of the government 379 people were killed and 1137 wounded.

But firing was not the end of the miseries of the people. Curfew was imposed and the wounded were left unattended throughout the night in the Jallianwala Bagh. Martial Law was imposed and men were killed on the slightest excuse. They were made to crawl and trail their noses in dust while passing through a certain street, where an English lady Miss Sherwood had been beaten by the mob on April 10. People were whipped in public. People riding in carriages had to get down from their vehicles on seeing any British and salute him. The tragedy of Jallianwala was kept a secret. Even Gandhiji learnt of it much later and expressed deep regret and protest. Gandhiji and Vallabhbhai demanded an enquiry to be instituted against Michael O’ Dwyer and General Dyer.

Vallabhbhai warned the public—“The coming generations have a claim on us, who are their trustees; if we leave them only a heritage of insults and dishonour, of what use would all the wealth and all the comforts be that we may leave to them? If we put up with these insults would it be a matter of surprise if for all time to came we are despised by civilized nations?”