Chapter-12

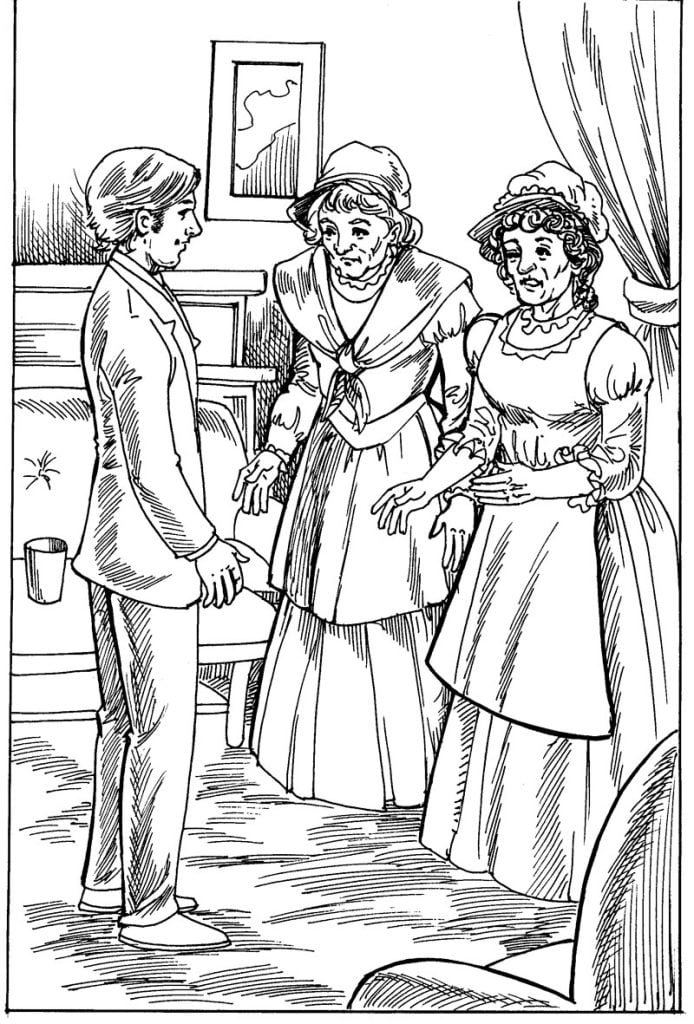

At last, an answer came from Dora’s two old aunts. I was welcome to visit them and discuss the proposed courtship in person. They specified a day and time, and told me I could bring along a trusted friend. As soon as I accepted their invitation and arranged for Tommy Traddles to accompany me there, I fell into a serious nervous agitation.

When the maid opened the door, I had a mild sensation of being on view. We went across a hall into a quiet drawing-room. The glass doors at back opened onto a garden. An old-fashioned mantel clock ticked steadily—in a rhythm that didn’t match my pounding heart. It seemed to tick a thousand times before the brittle, little, black-gowned sisters entered the room.

“Do be seated,” said one of them.

The sisters were birdlike, with bright and darting eyes and sudden mannerisms. They seemed to ruffle and adjust themselves, pertly and repeatedly, like canaries. Clarissa and Lavinia, as they called each other, were dressed alike, although the younger one wore her black dress with a perkier air—perhaps there was a little more frill to the sleeve or an extra bow. They both had excellent posture, formal and composed. One sister, the younger one, had my letter in her hand. The other kept her arms crossed over her breast and every few moments she seemed to tap out some unshared music on her upper arms.

“Mr Copperfield?” said the sister with the letter.

“My sister Lavinia,” said the younger woman, “will tell you what we believe will promote the greatest happiness of all parties concerned.”

“Thank you, Clarissa,” said the other.

Each of the sisters leaned a bit forward to speak, shook her head after speaking and straightened up in silence.

“We have no reason,” said Miss Lavinia, “to believe you are anything but an honourable young man. And we believe you care for our niece.”

Given to a bad case of excess at just that moment, I exclaimed that nobody had ever loved anybody as I loved Dora. Traddles murmured in solid agreement.

“We understand that you believe what you say, but we need to see for ourselves,” Miss Lavinia continued, “And so we agree to your request to visit Dora here—only here. Can you abide by that, Mr Copperfield?”

I bound myself immediately to the required promise.

The sisters laid out a schedule of visits—Sunday dinner at three o’ clock and tea at half-past six two evenings a week—and asked me to invite my aunt to visit them. Then they stood, said goodbye to Traddles and to me, and left us to the care of the mind who showed us out.

Now my full days were overflowing. Work in civil law, dictionary writing, parliament reporting, and courting! I lived for my times at Putney.

In all the excited bliss of this courtship there was one troublesome point for me. I saw the Spenlows, and indeed even Aunt Betsey, treating Dora like a child—no, more like a pet. She was pampered and spoiled, treated much the way she treated Jip. Dora didn’t seem to mind, though.

I was amazed when Dora asked me to give her a cookbook and to show her how to keep the household accounts according to my earlier suggestion. Within the week, however, the cookbook had made my love’s head ache and when the figures wouldn’t add up they made her cry, so all was put aside and life went on as before. Even I wondered occasionally if I’d slipped into the general fault of treating her like a pleasant child.

Mr Wickfield had business in London and Agnes travelled with him from Canterbury for a two-week stay. I arranged with Miss Lavinia to bring Agnes to tea so that she could meet Dora.

I was proud and nervous—proud of my beautiful Dora and worried sick that Agnes wouldn’t like her. But the gentle look on Agnes’ face shook all of my fears aside, and the two young women became instant friends. In fact, when we finally departed for town, Agnes had only good things to say of Dora, and I basked in the glow of her words like settling into warm sunlight.

Weeks, months, seasons passed—flew by so quickly that they felt like no more than a summer day and a winter evening. I left Doctors’ Commons and the civil law and took a job with the London Morning Chronicle as a reporter. I also began to write fiction. When my first piece, written and submitted in secret, was published in a popular magazine, I set to writing regularly and built a reputation among readers.

By my twenty-first birthday, my income had risen comfortably. The Spenlow sisters gave their happy consent, and Dora and I prepared to marry.

What a bustle of activity it was for everyone in our small families! Miss Lavinia took on the wardrobe task. Miss Clarissa and Aunt Betsey scoured London for furniture. Peggotty set to cleaning and recleaning, polishing and repolishing every inch of our new cottage. Agnes and Sophy, Traddles’ fiancée, outfitted themselves as bridesmaids, and Mr Bick practised time and again his conducting my precious Dora down the church aisle and onto my waiting arm.

The groom, however, remained in a fog. I felt misty and unsettled, as if I’d got up very early in the morning a week or two ago and hadn’t been to bed since. Nothing was real to the touch. It all swirled around me, like a dream I could see but not take part in a happy, flustered, hurried dream.

Then suddenly it was the wedding day. Senses were exaggerated: smells were stronger, colours brighter, sounds closer to my ears.

Dora came into the church with Mr Bick—lovely she was, grinning he was. Miss Lavinia was the first go sob. Aunt Betsey tried her best to be firm, but tears rolled down her face. Dora shook terribly at my side and made her wedding responses in tiny whispers, then collapsed in a massive cry for her dead father when we’d left the church. There was a wedding breakfast with tables full of food and champagne, and I made a toast to my bride and one to my dear family and friends.

The celebration drew to a close in the late afternoon. Traddles had hired a carriage with a white horse and decorated it with flowers and bows, and we rode away to the music of cheers and good wishes.

“Are you happy now, you foolish boy?” asked Dora, snuggling close beside me in the carriage, “Are you sure you don’t regret this?”

I kissed her nose and told her I was sure.

We settled into our married life. All of the romance and yearning of our engagement were put aside in the daily presence of one another.

We were so young and so unprepared to keep house, but we got used to it. We hired a housekeeper who did a passable job—but Dora took no part in managing the daily chores. I spent long hours at my writing and my dear wife sat beside me petting Jip and drawing pictures of flowers. Home was not as I might have wanted, but it was home nonetheless.