Chapter-3

We hadn’t gone half a mile, and my handkerchief was wet through with tears, when Peggotty burst through a hedgerow and flagged the driver to stop. She climbed into the car with me and squeezed me in her big, warm arms. Without a word she pulled from her pockets some paper bags of cookies and a change purse. These she crammed into the pockets of my jacket, gave me another powerful hug, and hopped down from the cart, signalling the driver to move on.

I watched the spot in the hedge where she disappeared until I could no longer see spot or hedge, then turned around and pulled the purse from my pocket. It was of stiff leather, with a snap, and inside were three bright coins, three shillings in all. There was also a small piece of paper folded over written, “For Davy. With my love.”

The driver took me to a public eating house where Mr Murdstone had sent money ahead for my dinner.

After dinner, it was time to board a coach for London. The ride was long, overnight and into the next day. My fellow passengers slept soundly and snored most of the night, but I don’t recall as much as napping.

When we got to the coach stop in London, there was no one to claim me. I went into the station and passed some time behind the counter with the clerk. My mind was in a flight. Suppose nobody ever came for me. Could I sleep at night in one of the wooden bins with the luggage, and wash at the pump in the horseyard? Was this the final part of Mr Murdstone’s elaborate plan to get rid of me? If I started off at once and tried to find my way back home, how far could I get before I was hopelessly lost? Could I join the Navy or the Army? Would they take such a little fellow? All of this had my mind in a fever when a man, unhealthy looking and poorly dressed, entered and whispered to the clerk, who lifted me off the baggage scales where I sat and handed me across the counter.

“You’re the new boy, I suppose,” he said quietly to me, “I’m a teacher at Salem House.”

He took me to a school enclosed by a high brick wall. A stout man with a bull-neck, a wooden leg, sagging jowls, and a close-cut cap of hair answered the door. We entered the courtyard in front of a square brick building with two wings and a bare and unfurnished appearance. It was perfectly silent. When I asked about this, I was told everyone was away on holiday and I was here early to begin my studies as a punishment.

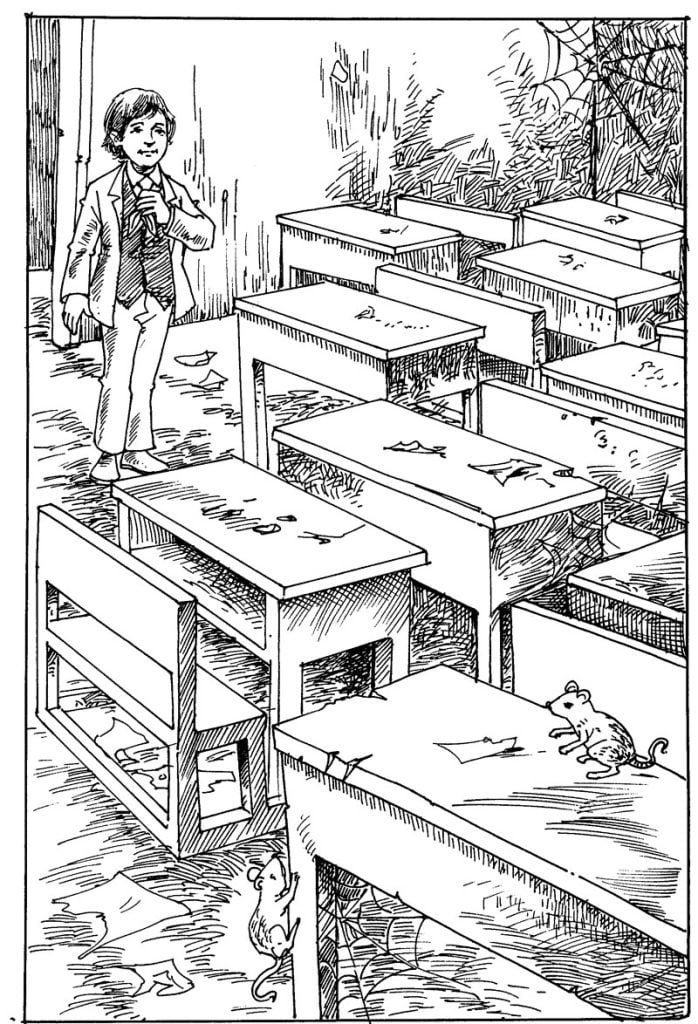

In the forlorn and desolate classroom papers and dirt covered the floor and desks; mice ran everywhere looking for food. My teacher, Mr Mell, took me to the back of the room, where I spied a cardboard sign, beautifully written, that bore the warning, “Beware of him. He bites.”

“Where’s the dog?” I asked Mr Mell.

“What dog?”

“Isn’t there a dog to wear this sign, sir?” I pointed to the cardboard.

“No, Copperfield,” Mr Mell said gravely, “I’m afraid that’s not a dog, but a boy. My instructions are to put this sign around your neck and hang it down your back. I’m sorry to do it, but I must.”

What I suffered from that sign nobody can imagine. I always thought someone was reading it and laughing at me or judging me to be hopeless. And in the weeks before the school filled up again with students, I lived in dread of their return and my humiliation. In later years as I recalled Salem House, I could see the dirty bricks, the green cracked flagstones in the courtyard, the discoloured trunks of some of the grim and dying trees. I could smell and feel the damp of the rooms. But more acutely than anything else, I remembered the sign and how I hated it.

I had been at my studies about a month when the school’s headmaster, Mr Creakle, and all the other boys returned from their holidays.

On the evening of Mr Creakle’s return, I was taken by Mr Tungay, the man with the wooden leg, to meet the headmaster. Mr Creakle had a snug garden space that looked like an oasis after the miniature-desert of a playground I had grown used to. I trembled as I followed the uneven clomp of Tungay’s leg down the passageway, and was led before a stout man with a flery face and little pig-eyes. There were thick veins in his forehead, above a small nose and a huge chin. He was bald on top, but some thin and wet-looking strands of greying hair were combed up and forward to meet just above his brows. What made the greatest impression on me was his voice—he had none, but spoke in a strained whisper that required such exertion as to make his angry face even more furious and his ropy veins even more bulging.

“So, this is the biter, is it?” said Mr Creakle when I took a place before his chair, “What’s the report on him?”

“Nothing against him yet, sir,” was the wooden-legged man’s response, “There’s been no chance for mischief.”

I thought Mr Creakle looked disappointed by this news.

“I have the happiness of knowing your step-father, Mr Murdstone,” whispered Mr Creakle, taking me by the ear with a nasty twist, “What a fine man of strong character!”

My ear took another painful pinch.

“Let me tell you something about myself,” he whispered menacingly. “When I say I’ll do a thing, I do it. And when I say I’ll have a thing done, I will have it done. Nothing gets in my way. Do you get that, boy? Now you begin to know me like the other boys do. Take him away.”

The first boy to come back, Tommy Traddles, appeared the next morning. He took real delight in my awful sign and saved me the embarrassment of either displaying or hiding it by presenting me to every other boy and getting the fun-making out of the way. Some of the boys couldn’t resist the temptation to pretend I was a dog and instructed me to roll over or sit up, but none of it was mean-spirited.

By the end of the day, I had met all the boys but one, James Steerforth, widely reputed to be the central figure among all the students. He was said to be a great scholar, extremely handsome, and at least half a dozen years older than I. When we met that might he pronounced my punishment a terrible shame—and became an instant friend.

Mr Creakle’s reputation for violence certainly was not exaggerated. On the first day of classes, the roar of voices in the classroom was suddenly silenced when Mr Creakle appeared in the doorway after breakfast. Mr Tungay waited to his left as his interpreter, ready to repeat in a shout what his master said in a whisper.

“Be silent!” shouted Tungay, although there was not a sound in the room. “Boys, this is a new semester,” he repeated for Mr Creakle. “Come prepared to learn; I advise you, because I come prepared to punish you. Now get to work.”

Creakle began his passage up and down the aisles of boys bent over their notebooks. He came to where I sat and told me that if I were famous for biting, he was famous for biting, too.

“What do you think of the teeth on this?” he asked, putting his fiery-faced whistle near my ear and snapping his cane whip across my legs. “Sharp, hey? A double set of teeth, hey? Has a deep bite, doesn’t it?” With every question, he let the cane cut into my back or my arms.

He greeted the majority of the boys in the room in a similar manner, doing so with enormous delight. Eventually, nearly every child present was crying or cowering in his seat.

In such an atmosphere, how, then, did I manage to pick up some crumbs of knowledge? It was because of the friends I had at Salem House, especially Tommy Traddles and James Steerforth. Tommy’s companion-ship in the face of our mutual adversity, and Steerforth’s steady championing of the interests of the younger and weaker boys went a long way towards protecting my spirit and some small way towards protecting my skin.

Steerforth was not usually punished like the rest of the boys. He was older and larger and his attitude suggested he was not much impressed by Creakle’s cane. In fact, Creakle and the teachers, even the brute with the wooden leg, generally left Steerforth alone. He was my protector and friend, although his protection did not keep me from regular beatings in and out of class.

And if it can be agreed that something good comes from even the most evil thing, in his severity Mr Creakle found the sign hanging down my back to be in his way when he hit me with the whip, so he ordered it removed for good.

In this fearful and tormented way, the semester passed. Most of the time is a jumble in my recollection: the ending of summer and the changing of all seasons; the frosty mornings when we were bell-clanged out of bed before dawn; the cold, cold smell of the dark nights when we huddled under light and scratchy blankets; the morning schoolroom, which was nothing but a great shivering machine; the daily choice of tasteless beef, boiled or roasted, and clods of bread-and-butter; the dog-eared books, cracked slates, tearstained notebooks; beatings with cane whips or rulers; and the grimy atmosphere of ink surrounding all.

At last, the holidays arrived. How strange it felt to be going home when it was not home, and to find that every object I packed reminded me of the happy old times—all like a dream that I could never dream again! I wondered as I travelled if it might not have been better to stay at school and remember things as I wished them to be. But soon I was at our house, where the bare old elm trees wrung their many hands in the bleak winter air and shreds of the old crows’ nests drifted away on the wind.

I jumped down from the coach at the garden gate and took the path towards the house, glancing at the windows and fearing to see Mr Murdstone or his metallic sister staring out at me. I opened the door silently and a sweet memory of my earliest years greeted me: my mother was humming a lullaby she had sung to me so long ago, her soft voice sweet and clear.

She was sitting by the fire as I took a timid step into the parlour.

“Mother,” I said quietly, and she came quickly across to me.

“Davy, my dear, dear boy! You’re home at last,” she said, hugging me long and close.

Peggotty, hearing our voices, came bounding in from the kitchen and we all plopped down on the carpet and laughed and hugged and cried.

Mr Murdstone and his sister were out on a visit and were not likely to return before night so we could spend our afternoon together as we had before out threesome was increased to five. We ate supper by the fireside. Peggotty brought out my old dinner plate with the large ship and stormy waters painted in the centre, and the mug with my name on it, and my little fork and the knife that wouldn’t cut.

We talked of neighbour and I shared the few happy stories of my life at Salem House telling all about Tommy and Steerforth and never mentioning Mr Creakle or Mr Tungay. I noticed that my mother, though she smiled a lot, seemed more serious and careworn. She was still pretty, but looked too delicate, so pale and thin she seemed transparent. Her hands trembled a bit and she was nervous.

After the dishes were cleared away, I moved close to mother’s side and sat with my arms around her waist. It was a wonderful evening. I sat looking at the fire and seeing pictures in the red-hot coals, almost believing that I had never been away, that the Murdstones were only such pictures that would vanish when the fire got low, and that there was nothing real in all that I remembered except my mother, Peggotty and I.

It was almost ten o’clock when we heard the sound of wheels by the gate. Mother hurried me to bed, and I gladly took a candle and went. It seemed to me, as I walked to the bed-room where I had been imprisoned, that the Murdstones’ arrival brought into the house a cold blast of air that blew away the old, familiar feelings like a feather in a gale.

I dreaded going down on breakfast the next morning, and in fact made several starts for the stairs only to run on tiptoe back to the shelter of my room. Mr Murdstone was standing by the fire in the parlour and Miss Murdstone was pouring tea when I finally went in.

He looked at me steadily, but made no sign of recognition.

After a moment of confusion, I went towards him and said, “I beg your pardon, sir. I am very sorry for what I did and I hope you will forgive me.”

“I’m glad to hear you’re sorry, David,” he said, putting the once-bitten hand out for a brief shake, then turning away from me entirely.

“Dear me,” sighed Miss Murdstone, “How long are the holidays?”

“A month, ma’am,” I said.

“Counting from when?”

“From today, ma’am.”

“Oh,” she puffed, “then there’s one day off.”

Each morning she took her calendar and checked off a day. She did it gloomily until she came to ten, and then became more hopeful. As the page filled with Xs, she turned almost pleasant.

The holidays slogged by until the morning came when Miss Murdstone made her last X and said, “Here’s the last day off!”

I wasn’t sorry to go, for I was looking forward to Steerforth and Tommy. I kissed Peggotty and my mother, and knew that I would miss them, but there was a gulf between us and the parting had been there every day of my vacation. I took with me the memories that would best keep me and left behind those that hurt.

I had been back at Salem House two months when my tenth birthday dawned. The morning class had only begun when one of the schoolmasters sent me to the parlour. It must be a box of birthday cookies and treats from Peggotty, thoughts as I hurried down the hallway. Something to brighten the day for me and the other boys, for anyone lucky enough to receive packages share any food received with every other boy.

I skidded around the open parlour door practically knocking Mrs Creakle to the floor. She held an opened letter in her hand, but there was no box of treats in sight.

“David Copperfield,” she said, leading me to a sofa and sitting down beside me, “I have something to tell you, child.”

She glanced at the letter on her lap and took my hand in hers. “It’s a bad lesson, but we all have to learn it some time, some of us when we’re young. Was your mother ill when you were home for vacation?” she asked.

I felt a chill even colder than the day. “No, ma’am,” I whispered, the tears beginning to run from my eyes before I knew how bad the news would be.

“She’s dead,” was all I heard Mrs Creakle say, although it seemed her mouth kept moving as I stared through the blur of tears.

Mrs Creakle kept me with her all day, sometimes sitting and holding me while I cried, sometimes leaving me alone with my thoughts and my sadness. I thought of our house closed up and hushed, and for the first time I felt truly an orphan in the world.

The next afternoon I left Salem House, travelling by coach to Yarmouth and then on to Suffolk. The long and unhappy trip ended at the garden gate, and I was in Peggotty’s strong arms before I got close to the kitchen door. We cried for some time, kneeling on the stone walkway, then finally she scooped me up and bundled me inside, all the time talking in whispers to calm herself and me.

I sat for a while in the parlour where the only sound was the hiss and crackle of logs on the fire. Mr Murdstone sometimes would walk from chair to table to sofa and then to chair again. He seemed to be the only restless thing except the clocks, in the whole motionless house.

On the third day, we gathered around an open space in the neighbouring churchyard, beside my father’s gravestone, and heard prayers spoken over the only family I had. Soon it was finished and we walked back to the garden gate and into the kitchen.

“She wasn’t well for a long time, Davy,” said Peggotty. “And she wasn’t happy. She seemed to get weaker every day. But, Davy, the last time I saw her acting anything like her old self was the night you came home for vacation. She loved you, don’t you ever forget.”

I sat that evening in the parlour, alone with my earliest recollections of my mother, thinking of her winding her curls round and round her index finger, and dancing and laughing with me at twilight in that very room.